Everywhere at the End of Time

Everywhere at the End of Time is the first series of albums by the Caretaker, released from 2016 to 2019 by English electronic musician James Leyland Kirby on his own self-operated record label History Always Favours The Winners. After the release of An Empty Bliss Beyond This World, Kirby felt a need to produce more music of its style approaching the Alzheimer's-related themes the album had tackled. The series samples various big band records and manipulates them in order to produce an artistic depiction of dementia; it degrades the melodical coherence of each track and shifts its sound into more experimental styles of music as each stage progresses. Eventually, the series climaxes on its last 5 minutes by presenting a clear choral song and a minute of silence, which are hypothesized to be representations of the terminal lucidity phenomenon and the patient's death respectively.

| Everywhere at the End of Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

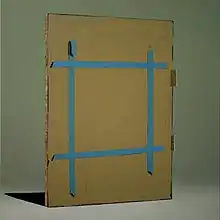

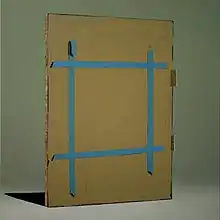

Cover art for the last release of the series, Stage 6. | ||||

| Recording by the Caretaker | ||||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 390:32 | |||

| Label | History Always Favours the Winners | |||

| Producer | James Leyland Kirby | |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

The release features Kirby turning the Caretaker alias itself into a character by "giving the project dementia," ending with the retirement and canonical death of it on 2019 when Stage 6 and its accompanying compilation album Everywhere, an Empty Bliss were released. The album covers are oil paintings created by Leyland Kirby's long-time friend Ivan Seal, and have been regarded as integral to the experience of the record. It was met with a generally positive reception from music critics, who have praised the way the series depicts the disease, and became popularized by various YouTube videos that considered the album's themes as disturbing throughout the year of 2020.

In October 2020, the album series became further popularized as an online challenge on TikTok, with users challenging each other to listen to the project in full due to its long length. While its popularity on the platform has received negative backlash from some users, due to some of the TikTok users implementing creepypasta elements to the record rather than considering it "a real depiction of a deadly disease," Kirby stated it would be good for independent music to gain notability, while Brian Browne from Dementia Care Education stated the record's depiction of dementia might help a younger generation to empathize with patients. The series' official YouTube upload view rate has been increasing exponentially since the album's popularity in 2020, achieving 10 million views in April 2021.

Background

The Caretaker was an alias created by English electronic musician James Leyland Kirby that sampled various 78-rpm recordings from the 1920s and 1930s.[1] Although his first albums were initially inspired by The Shining,[2], with the alias' name being taken from one of the characters in the film,[3] the project's notability increased when Kirby decided to implement themes of memory loss on his albums with the release of Theoretically Pure Anterograde Amnesia, a compilation of 72 .mp3 files exploring the disease of the album title, receiving positive reception from music critics.[4] The 2008 release Persistent Repetition of Phrases marked Kirby's change of record labels, shifting from V/Vm Test Records to History Always Favours the Winners.[5] It received further attention and also marked a notable change in style from the Caretaker's previous releases, featuring Alzheimer's disease as its main theme rather than amnesia.[6]

In 2011, the Caretaker released An Empty Bliss Beyond This World, a record based on a 2010 study about how music can help Alzheimer's patients in remembering new information.[7] The release had gained further attention from critics at the time, being named the 14th best ambient album of all time by Pitchfork.[8] Some of the record's samples would eventually return on the third album of Everywhere at the End of Time. Kirby revealed that, despite the success of his 2011 release, he did not plan out making it, and the album was made because of "pure chance in action at all times."[9] In an interview with Bandcamp, the musician stated that, even though he initially did not want to produce another Caretaker record, the reception An Empty Bliss had gained inspired Kirby to release a series of albums expanding its concept, as he now had a larger audience to which he could expand the record's themes upon.[10]

Concept, composition, and production

The complete edition of Everywhere at the End of Time is divided into six individual albums, titled "stages," which are musical depictions of common symptoms a dementia patient suffers with.[11] In an interview with Landon Bates from The Believer, Leyland Kirby described the first three stages as having "subtle but crucial differences, based on the mood and the awareness that a person with the condition would feel", adding that the final three stages "had to be made from the viewpoint of post-awareness;" while each composition in the first three stages features a single sample changed through pitch changes, reverberation, looping, crackle and physical degradation, those on the latter three feature multiple samples woven together in a sound collage format which Kirby has likened to John Cage's usage of chance in music.[12] The sound in the later stages is constructed from radical manipulations of samples which had previously appeared in Stages 1–3 or in other Caretaker projects. In making Stages 4 and 5, Kirby claimed that he had over 200 hours worth of music and "compiled it based on mood" using cutting-edge digital technology.[1] Stage 6 consists of drones and dark ambient sounds as well as a choral recording within the last six minutes to mark the end of the Caretaker.

While Kirby has often stated he would be more focused on producing the last three stages, he added the first three are still "essential" to the series, as they provide the context to the latter stages.[1] On a video interview with Alexandre Bazin, Kirby revealed the sound collages of the latter stages require large amounts of computing power, adding that the background noise effects have to sound organic, in order for the listener to "not know the process but know things are falling apart."[13] The musician further revealed one of the biggest challenges he had while producing the last stages was what were "the best 40 or 50 minutes" to include of what he claimed to be over 250 hours of recordings, further noticing Stages 4 and 5 were not how he had expected them to be, as he tried to create a "listenable chaos."[12][13]

Kirby calls the last three albums the "stages of diminishing returns," as he'd expect his audience who enjoyed his previous albums to not like them.[12] For the first three stages, Kirby stated one of his "strategies" has been to use different versions of the same samples for achieving certain emotional messages with each different version of the sample; while the sample of the first track from the first stage has been described by Kirby as upbeat, the third track from the first stage, which uses the same sample but a different cover of it, has been described by him as "somehow sounding low."[14]

Stage 1

| Everywhere at the End of Time - Stage 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released | 22 September 2016 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 41:31 | |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Here we experience the first signs of memory loss.

This stage is most like a beautiful daydream.

The glory of old age and recollection.

The last of the great days."— Leyland Kirby[16]

Like An Empty Bliss Beyond This World, Stage 1 consists of the first seconds from several 78-rpm jazz records from the 1920s to the 1940s slowed down and played in loop for long periods of time, being mostly composed of snippets of ballroom music repeated ad nauseam.[17] This stage presents twelve tracks, with six tracks occupying vinyl sides A and B.[18] The music is surrounded by a subtle static background noise.[19] As the first stage of the entire project, it is the lightest stage despite its typically looped composition, due to being early on in the dementia process.[18] Most of the tracks present an upbeat and positive style, with only a few taking on a slower pace.[20] The only methods of alteration Kirby makes to the samples are adding reverberation and looping sections to create longer pieces, as well as emphasizing the existing vinyl crackle in the mix. In making the first stage, Kirby described the mastering, as done by LUPO, to be "really rich, really big, really consistent sounding all the way through".[14] Track titles from this stage also suggest a comforting sense, with names such as "Late afternoon drifting," "Childishly fresh eyes," and "The loves of my entire life."[15]

– Leyland Kirby[14]

Kirby described the opening track, numbered as track A1 and titled "It's just a burning memory," as very upbeat, "nice and really warm."[14] Track A2, "We don't have many days," samples a cover of "Say It Isn't So" by Layton & Johnstone, which has caused some writers to describe the stage as "a surreal version of Name That Tune."[21] Track A4, "Childishly fresh eyes," has been described as suggesting "barely remembered muzak, and is superficially soothing."[21] While Pat Beane from Tiny Mix Tapes wrote that the repeating brass lines of track A4 have a "splendor" to it, they were "unsteady" when combined with the piano presented on track A5, "Slightly bewildered,"[22] a track also described by Brian Howe from Pitchfork as presenting an "almost toneless mooing;"[23] the track presents a pianist performing but "just not getting it right," which makes it, as wrote by Pat Padua from Spectrum Culture, "mildly disorienting."[21] Howe from Pitchfork, however, praised the "inner humming voice" from track A6, "Things that are beautiful and transient."[23] Songs from Side B, such as track B2, "An autumnal equinox," and track B4, "The loves of my entire life," have been described by Howe as possessing "a winning gentleness."[23] However, the writer adds that by the end, "even gentleness has taken on a desperate tinge, as though if the dancing stops, everyone dies."[23] The record ends with, as described by Beane, "melodramatic swells" found on track B6, "My heart will stop in joy," which ends the album with an echoing horn section that some writers described by Padua as having a sound similar to "the pinnacle of big band ballroom romance."[21][22]

The album cover is titled Beaten Frowns After.[24] It depicts a stationary unraveling grey paper scroll resting on a blue gradient horizon.[25] Pat Beane likened the object to the creases of the brain, adding it "seems petrified as a statue, stuck in the pose of discomposure, without revealing anything of its history," and that its simpleness forebodes the tracks of the album, considered "brilliant" by him.[22] Sydney Leahy from The Blue & Gold stated the artwork could have been chosen to depict the patient's knowledge that, "as the disease evolves, their ability to remember recent events may become completely dysfunctional."[25]

Stage 2

| Everywhere at the End of Time - Stage 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released | 6 April 2017 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 41:55 | |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

"The second stage is the self realisation and awareness that something is wrong with a refusal to accept that. More effort is made to remember so memories can be more long form with a little more deterioration in quality. The overall personal mood is generally lower than the first stage and at a point before confusion starts setting in."

— Leyland Kirby[16]

Stage 2 shifts its focus to the denial/acceptance of the disease by the patient.[20] This stage presents ten tracks, with five tracks occupying vinyl sides C and D.[26] It presents a much more melancholic tone, featuring a more distant style of music.[20][27] Its track titles present more somber themes as well, with names such as "Surrendering to despair," "Quiet dusk coming early," and "The way ahead feels lonely."[28] The music in this stage is much less direct, with some of the tracks being thought by some writers as having a light use of field recordings complementing the sampled songs.[20] In an interview with The Quietus, Kirby described the "switch" between the first and second album, specifically noting that instead of looping short sections of sampled material as with the first stage, he would let tracks play in full while stripping certain sections away, not necessarily making them composed of only small loops.[14]

– Leyland Kirby[14]

The opening track of Stage 2, "A losing battle is raging," features a more drone-inspired style which has been compared by Holly Hazelwood from Spectrum Culture to the music of Boards of Canada, with the writer adding that its sound, instead of conveying gentleness, is "cloaked in heavy sorrow;"[15] the song has been described by Boomkat as having a "fading beauty" to it.[28] Track C3, "What does it matter how my heart breaks," features the same sample as "It's just a burning memory,"[29] The track uses the Seger Ellis cover of the original song, which in this stage has been described as "plagued with lethargy."[15][30] On Boomkat's product review for Stage 2, track C4, "Glimpses of hope in trying times," has been described as presenting a more tense style, before track D1, "I still feel though as I am me," basks in "glowing embers" that turn to track D2, "Quiet dusk coming early."[28] Track D3, "Last moments of pure recall," features a far more upbeat style than other tracks in the album, being described as a "waltzing" bliss by Boomkat.[28] The pair of track D3 with track D4, "Denial unravelling," has been hypothesized to be the patient no longer having the ability to pretend that they are well.[15] Boomkat concluded this further ends with the "unshakeable pangs of sadness" that compose track D5, "The way ahead feels lonely."[28]

The album cover is titled Pittor Pickgown in Khatheinstersper.[31] It depicts an abstract flower pot with four flowers inside. The lower section of the pot features sculptures of two faceless humanoid figures, one male and one female. Frank Falisi from Tiny Mix Tapes wrote that, while the scroll presented in the album art of Stage 1 was a reminder that "the only thing behind our bodies is us," the album cover for Stage 2 is what is presented when the scroll becomes unfurled, adding that "the only things behind our bodies are pretty flowers from a rotten rock."[29]

Stage 3

| Everywhere at the End of Time - Stage 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released | 28 September 2017 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 45:36 | |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Here we are presented with some of the last coherent memories before confusion fully rolls in and the grey mists form and fade away. Finest moments have been remembered, the musical flow in places is more confused and tangled. As we progress some singular memories become more disturbed, isolated, broken and distant. These are the last embers of awareness before we enter the post awareness stages."

— Leyland Kirby[16]

Stage 3 is the final stage in which samples are recognizable as their original melodies. This stage presents sixteen tracks, with eight tracks occupying vinyl sides E and F.[32] This album starts "breaking the songs down," presenting reverberation and static noise over notes.[27] The track titles on Stage 3 are nonsensical rearrangements of the song names from either Stage 2, Stage 1, or An Empty Bliss, a fact hypothesized to be the memories of a patient becoming more and more confused.[30] As an example, track E3, "Hidden sea buried deep," takes its title from "The great hidden sea of the unconscious" and "Bedded deep in long term memory." Some samples from Stage 1 return in this record, although they "sound like they've taken on water."[15] In this album, some of the songs end abruptly, colliding with the ones that follow.[15] This record has been noticed by Kirby as the most similar to his previous project An Empty Bliss Beyond This World, for featuring many samples which have been taken from the entire project's history.[14] The album cover is titled Hag.[33] It is the first artwork in the series to present an unrecognizable object, with Sydney Leahy stating it "appears" to be a kelp.[25]

– Leyland Kirby[14]

Track E1, "Back there Benjamin," has been described as "a confused mishmash of chaotic, loud music," which Beach Sloth from Entropy has also noted due to its "bled-dry jaunt."[34] Track E2, "And heart breaks," is the last coherent version of "Heartaches," presenting its element collapsing.[15] The melody of track E6, "Sublime beyond loss," has been hypothesized to be Kirby deliberately confusing it, "letting it become lost, impossible to truly focus [on]."[34] Track E8, "Long term dusk glimpses," has been described by Sloth as the "true heart" of the record, for presenting a melody that seemingly fights the memory loss, "at times becoming defiant against its doomed fate."[34] Side F is made up of much shorter tracks with less amount of their original samples recognizable, which have been described by writer Michael Barnett as the point where Kirby takes "an interesting turn" for featuring a more dark ambient-inspired style on tracks such as F3, "Internal bewildered World."[35] Track F4, "Burning despair does ache," is the last coherent version of "Heartaches," which sounds normal at the beginning but eventually presents glitch effects in its melody.[30] Track F5, "Aching cavern without lucidity," has been described by Barnett as little more than a "droning murky memory" from what the previous tracks presented.[35]

Stage 4

| Everywhere at the End of Time - Stage 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released | 5 April 2018 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 87:21 | |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Post-Awareness Stage 4 is where serenity and the ability to recall singular memories gives way to confusions and horror. It's the beginning of an eventual process where all memories begin to become more fluid through entanglements, repetition and rupture."

— Leyland Kirby[16]

While the first three stages featured the same style of the Caretaker's previous releases, featuring melodies and repeating structures, the compositional aspects of Stage 4 are more similar to noise.[30][15] It marks the beginning of the Post-Awareness stages, where individual tracks are not short and taken from one sample but rather 20 minutes long and featuring changing sections, occupying whole vinyl sides.[36] In an interview with The Believer, Kirby coined the term "Post-Awareness" as the stages where a patient is unaware of their dementia, a term already known as anosognosia.[12] The tracks occupy whole vinyl sides and present more medical terms; while each track in the first three stages presented a traditional naming system, Stage 4 presents four clinical names on its tracks: three of them (tracks G1, H1, and J1) titled "Post Awareness Confusions" and one of them (track I1) titled "Temporary Bliss State."[37] According to Andrew O'Keefe from No Wave, while coherent melodies are much harder to grasp, they are presented only when it is necessary to provide emotional weight in contrast to the chaos around them, "shedding the mysterious poetry of earlier stages."[38]

The "Post Awareness Confusions" tracks feature distorted snippets of instruments from either the previous stages of the project or from Kirby's previous releases as the Caretaker.[35] A part of them samples Russ Morgan's "Goodnight, My Beautiful" and adds heavy glitch and distortion effects to it, which makes the original sample nearly unrecognizable.[39] According to Miles Bowe from Pitchfork, they capture the "darkest, most damaged" noises of the entire series, either by "dwelling on one ghostly sample" for long periods of time or by "violently accelerating through skipping melodies" which Bowe has compared to Oval's ambient release 94 Diskont.[39] Other writers interpreted the sound of the album as the noise of an AM radio stuck permanently between two different stations.[15] These tracks present an increase in the noticeable static of their sound, re-configuring the Caretaker's signature horn samples into "distorted new shapes" or to their limit.[35][40] According to Sam Goldner from Tiny Mix Tapes, while noise was presented in previous Caretaker releases simply as a background effect, these tracks feature it becoming the music's "primary driving force, pushing the pieces in all directions at once with vivid, cacophonous force."[40]

Tracks G1 and H1 start the album with "an explosion of panic," being described as the "most visceral" of the record.[38] The composition of track H1 is considered to have "an almost unbearable stretch of dark, judgement-day horns."[38] One of the sections in track H1 has been dubbed as the "Hell Sirens" by the Caretaker community, due to it presenting a horn sample distorted to the point where "it sounds like an alarm from the deepest pits of Hell," being considered by listeners as the peak of the series in terms of terror/horror; the segment presents a howling foghorn and wailing sirens that have been described by some commentators as sounding "ike the screams of the damned,"[30] being described by Holly Hazelwood from Spectrum Culture as one of the most horrifying moments in the series.[15] Track J1 presents an abrupt ending that, in the words of Bowe, makes the record "[even] more devastating."[39] Holly Hazelwood from Spectrum Culture analyzed that, due to J1 being presented after track I1, "Temporary Bliss State," it is a way to "punish the subject for having escaped for as long as they did."[15]

The album's tone becomes less melancholic when track I1, "Temporary Bliss State" plays, as the track presents a less distorted sound.[38] While still incoherent, it presents a much less harsh sound when compared to the first two tracks.[35] On the track, Kirby leaves no trace of the ballroom samples that are usually associated with the series but instead warps its source material into, as Bowe wrote, "pure ethereal abstraction;" while the critic stated that the "Confusions" tracks reach "unexplored extremes" for the Caretaker, the "dreamlike" aspects of I1 were described by him as even more disorienting than any of the "Confusions" tracks, yet being "so beautiful it barely sounds like the Caretaker at all."[39] Holly Hazelwood stated that the track is meant to be treasured since, "as the title makes clear, it’s temporary."[15]

The album cover is titled Glitsholder.[24] While the previous artworks mainly presented simple everyday objects, Glitsholder is the first one to depict a human shape, which is seemingly facing away from the observer; Sam Goldner wrote the human form is presented "in the ashes of this dissolution," adding that "from the heart of death, a new life emerges, albeit one whose face we can’t see;" the writer further stated the human in the cover seems to be smiling when looked at from a distance.[40] Sydney Leahy stated Glitsholder is the "saddest, most striking" artwork to her, adding that the cover symbolizes the patient losing the ability to recognize his relatives.[25]

Stage 5

| Everywhere at the End of Time - Stage 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released | 20 September 2018 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 88:21 | |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Post-Awareness Stage 5 confusions and horror.

More extreme entanglements, repetition and rupture can give way to

calmer moments. The unfamiliar may sound and feel familiar.

Time is often spent only in the moment leading to isolation."— Leyland Kirby[16]

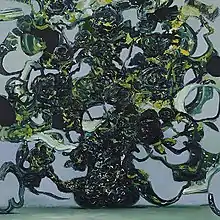

Stage 5 further expands its noise and experimental genre influence,[30] featuring a much more aggressive and intense style than its predecessors.[41] This stage presents even more medical terms within its track titles, such as "Advanced plaque entanglements." It is the first stage to prominently present human sounds, such as incomprehensible voices and distorted whistling; while the most part of it is incomprehensible, due to the syllables of the voices being discontinued, some tracks feature a clean use of it, presenting dialogue.[41][38] Some writers described it as the most agonizing stage of the entire project, due to the melody "ceas[ing] to matter," while others stated it presents a bit of all Post-Awareness stages' styles within it, due to its aggressiveness at the beginning, which is associated with Stage 4, and its emptiness at the end, which is associated with Stage 6.[15][38] This stage also presents the largest amount of layers of samples woven together, which makes them, according to Holly Hazelwood, serve no purpose but to pile upon each other, "an auditory traffic jam."[15] James Catchpole stated it represents some of Kirby's "most complex, experimental work."[41] The album cover is titled Eptitranxisticemestionscers Desending.[31] As suggested by its name, it is the most abstract artwork of the entire series; the most accepted hypothesis is that the artwork depicts a highly distorted, vaguely humanoid ballerina descending through a staircase.[30] Holly Hazelwood claimed it presents a "cancerous mass blooming out of a marble staircase," adding it symbolizes the patient's mind being "a remnant of a once-grand world, almost entirely unrecognizable."[15] TV Tropes classified it as being under the "Design Student's Orgasm" trope, describing the artwork as 'very ambiguous.'[30] As Sydney Leahy analyzed, the cover for Stage 5 becomes completely indiscernible.[25]

– Leyland Kirby[12]

After approximately 4 minutes from the start of track K1, "Advanced plaque entanglements," the intense noise abruptly cuts out and is replaced with a short big band sample presenting the style usually associated with the first three stages, before abruptly cutting out back to the intense noise usually associated with the fifth stage.[30] After approximately 15 additional minutes, the distorted voice of John Philip Sousa saying "this selection will be a mandolin solo by Mister James Fitzgerald" can be heard, followed by a mandolin sample from "Invincible Eagle March" by James Fitzgerald.[42] While also featuring a relatively calm and clear melody, the mandolin is heavily distorted, due to its original sample being a phonograph cylinder.[30][42] As the record progresses, its style shifts into a more extreme drone style.[30] Track L1, also titled "Advanced plaque entanglements," has been described by Holly Hazelwood as a challenge to the listener to find comfort within the "ambient horror we traverse."[15] Track M1, "Synapse retrogenesis," takes its title from synapses and retrogenesis, a hypothesis that suggests an Alzheimer's patient deals with the reverse neural development an infant goes through,[43] which Hazelwood further described as having an inhumanity to it.[15] Andrew O'Keefe from No Wave stated that the general style of this stage presents a feeling of "misfiring neurones, connections which cannot be made," further hypothesizing that the patient's memories were presented to the listener in the first three stages in order to "erode away" on the Post-Awareness stages.[38] As O'Keefe analyzed, by the end of track N1, "Sudden time regression into isolation," there is "barely a whisper to be heard."[38]

Stage 6

| Everywhere at the End of Time - Stage 6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by the Caretaker | ||||

| Released | 14 March 2019 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 85:58 | |||

| The Caretaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Post-Awareness Stage 6 is without description."

— Leyland Kirby[16]

Stage 6 mainly consists of deep static ambient noises, marking more emphasis on the melancholy of the patient rather than the chaos of the brain.[30] While Stages 4 and 5 mainly presented harsh noise, symbolizing the patient's memories falling apart, Stage 6 presents lengthy but empty compositions, which have been described by some users as "emptier than nothingness itself, the sonic embodiment of an almost completely empty mind."[30] Before its release, many listeners feared Stage 6 being a wall of harsh noise, which "areas like RateYourMusic comment boxes have proven records of."[30] It presents no detail whatsoever, which Holly Hazelwood has likened to the movement of a slow glacier.[15] Track titles from Stage 6, such as "A brutal bliss beyond this empty defeat," are less clinical but present more emotional statements.[15] Andrew O'Keefe stated that, although this stage mainly presents a drone style, "almost all talk about this final stage will centre on its shocking, and deeply human, conclusion as we follow the project to its death."[38]

Stages have all been artistic reflections of specific symptoms which can be common with the progression and advancement of the

different forms of Alzheimer's.

Thanks always for your support of this series of works

remembered by The Caretaker.

May the ballroom remain eternal.

C'est fini.

– Leyland Kirby[16]

The opening track, "A confusion so thick you forget forgetting," was noticed by Andrew Ryce from Resident Advisor due to presenting "foreboding" drones in its composition,[44] described by The Quietus as a "billowing fog of noise and raining hiss."[45] It does not present any recognizable part of the Caretaker's "established sound," but instead, features a "vast, cavernous, and upsetting" production,[45] described by Frank Falisi from Tiny Mix Tapes as "the void space around spent electric, the hot of last energy."[46] Track P1, "A brutal bliss beyond this empty defeat," was hypothesized by Ryce to be seemingly designed to "drive the listener to madness," due to its composition of repetitive noises and discordant notes;[44] as Falisi hypothesized, it is "the powder after bone ground on bone."[46] The Quietus further described track P1 as an ambient sound that symbolizes panic; while Stages 4 and 5 still featured brief flashes of instruments, P1 presents "echoes of anxiety," an enhancement of the "wholly peculiar and paradoxical nature of what you’re hearing."[45] Track Q1, "Long decline is over," features snatches of music hidden by obfuscating layers of static noise, where the music remains, as Ryce wrote, "frustratingly" out of reach: "at times you can sense it's there, but it's impossible to make out."[44] James Catchpole stated it introduces "an unexpected feeling of sublime peace;" as the writer analyzed, "the big band’s blurred melodies echo down the elongated hallway, calling out and ballooning, growing in volume."[47]

The final track of the album, "Place in the World fades away," presents the same sounds of the entirety of track Q1 on its first 6 minutes.[48] Eventually, a sustained organ drone begins to build up, which The Quietus described as something trying to break through.[45] Catchpole hypothesized it might be sampling a part of the Caretaker's previous release Deleted Scenes, Forgotten Dreams.[47] The organ gets gradually lower in intensity as the track progresses, before eventually abruptly cutting out to the sound of a vinyl needle hitting a record, six minutes before the ending of the album.[15] The last six minutes present the style and coherence usually associated with the first three stages of the project, sampling the track "Friends past reunited" which had previously appeared on the Caretaker's debut and second studio albums, Selected Memories from the Haunted Ballroom and A Stairway to the Stars respectively.[30] The song samples an excerpt of the German aria "Laßt mich ihn nur noch einmal küssen" from the St Luke Passion, BWV 246.[49] The entire series ends with a singular minute of silence, representing the end of the Caretaker alias and symbolizing the death of an Alzheimer's patient, as one minute of silence is usually the mandatory default time for paying respects to a dead individual or a group of individuals.[44]

Several writers have described an emotional response when listening to the final segment of the project,[45][47][46] along with several interpretations being formed surrounding the last minutes of the album, due to it being an unexpected moment where music returns after a long time of static noise.[30] The most accepted hypothesis is that the moment is a representation of terminal lucidity, a rare phenomenon where dementia patients suddenly regain their memory hours before death.[15] Other interpretations include the last six minutes being the funeral of the character, the soul of the patient moving on to the afterlife, or simply death.[30][49] Ryce suggested that what is being portrayed might be "a kind of oblivion,"[44] while Catchpole described the moment as perhaps "the brain hallucinating all along."[47]

The album cover is titled Necrotomigaud.[31] The artwork is generally thought to be a depiction of an empty canvas or the back of a picture frame with four strips of blue painter's tape, being described by Andrew Ryce as "meaningless and flattening."[44] It is also thought to be the patient being reduced to a completely blank canvas, with some commentators adding that the invisibility of the other side is a representation of all the life experiences of the patient no longer being accessible to them, due to the late stages of dementia having "destroyed" their ability to think.[30] However, Sydney Leahy's article on Everywhere at the End of Time stated the artwork depicts "a singular art board with four pieces of blue tape," adding it also serves as "the embodiment of nothingness."[25]

Artwork and packaging

The album covers for Everywhere at the End of Time are oil paintings created by Kirby's long-time friend Ivan Seal.[50] They are minimalist in their styles, often presenting a single object in a featureless room with no text.[30] They become more abstract with each stage, symbolizing the deterioration dementia causes to the brain.[25] When asked why the album covers and packaging did not present track listings, liner notes, or even the name "the Caretaker," Kirby stated Seal's paintings for the individual albums are "so important to each stage," adding that his name or text there is "unimportant," and that he's "honored" Seal lets him use his works as covers; the musician further wrote that they are "trying to not spoil the works so much with over-elaborate notes and text," concluding that, by having no text at all on the covers, there is a higher allowance of "space for personal interpretation."[12]

Several writers and music critics have praised the album covers of Everywhere at the End of Time, due to their abstract style. Holly Hazelwood noted that the "remarkable" art, as well as the song titles, as "integral" to the narrative of the record.[15] The abstraction of the album covers was described by Sydney Leahy to be giving "a familiar yet strikingly foreign feel" to them, adding this is due to Seal's paintings being created entirely from his memory.[25] When reviewing the sixth stage, Boomkat stated that, when combined with Seal's style of art, the project becomes "crystallised as a real gesamtkunstwerk for these times."[51] Richard Allen from A Closer Listen felt that Seal's art has always been integral to the Caretaker's music, as it offers "a visual corollary to the music," where its abstract style suggests that there is "beauty in this destruction that would not have been apparent had these subjects remained whole."[52]

Writing for German music magazine Betreutes Proggen, Benjamin Feiner complimented the paintings, due to their representations of everyday objects being seemingly "melted together," adding Seal's work with the Caretaker's music "fertilize and compliment each other, are made for each other."[53][54] Italian news website CyberDude wrote of the album covers as reflecting dementia, as they initially appear to be easily recognizable objects, such as a book on Stage 1, a vase and flowers on Stage 2, and the face of a woman on Stage 4; however are further presented as unrecognizable when paying attention.[55][56] Spanish writer Andrés Rojo from La Gramola de Keith stated one of the many reasons the project, as he opined, "will go down in history," are the album covers, which have been described as "beautiful."[57][58]

Ivan Seal's art and the Caretaker's music were the subject of a French art exhibition done in 2019 by FRAC Auvergne, featuring music from Everywhere at the End of Time along with an altered CD edition of Everywhere, an Empty Bliss and a book featuring Seal's art.[59] In the exhibition's description, it was revealed that both artists have similar visions: while Kirby presents music that surrounds themes of the failings of memory, Seal paints objects based on distant memories from his childhood.[60] ARTnews writer Andy Battaglia further suggested that:

"[Ivan] Seal and the Caretaker have a history. Both are from England and spent time together in Berlin, and they collaborated on a number of record covers for a project that just wrapped up with a six-album series devoted to thinking through memory loss and dementia. Music by the Caretaker (whose name is a nod to a spectral character in the 1980 Stanley Kubrick film The Shining) tends toward technologically altered reminiscences of the old-fashioned, with sounds of vintage ballroom waltzes and parlor tunes from 1930s-era 78-rpm records edited and processed into simultaneously straightforward and ghostly lull. And paintings by Seal tend toward the uncanny, with a representational simplicity locked in a tense duel with a habit for seeming to always be silently thinking out loud. Together, their work in different mediums found a match."[50]

Release

Kirby's initial idea for Everywhere at the End of Time was making one recording and degrade it over the course of three years; however, he stated in an interview with The Quietus his final idea has been to "give the whole project dementia." Kirby revealed the series' source material would be what he remembered from the project itself, later developing the idea of releasing six albums with a gap of six months between them to give, as wrote by him, "a sense of time passing."[14] According to Kirby, the six-month gaps between the releases of each stage are meant to represent an outside observer checking in on the Caretaker periodically and seeing a snapshot of their mental state at that point in time; depending on interpretation, this can mean the Caretaker suffered with dementia over the course of three years.[61]

The first stage of Everywhere at the End of Time was released on 22 September 2016. Kirby revealed the series would be "exploring dementia, its advancement, and its totality," adding each stage would "reveal new points of progression, loss and disintegration. Progressively falling further and further towards the abyss of complete memory loss and nothingness." He later stated in an email to Pitchfork he himself did not have dementia; only the project had.[62] This has caused some confusion within some websites, with music news publication Raven Sings the Blues mistakenly writing an article stating Kirby had been diagnosed with early-onset dementia;[63] writing for Pitchfork, Kirby stated there shouldn't be any confusion and "it's not intentional if there is any," adding that ending the project by "giving it dementia" is "a fitting epitaph for a finite series of works which has always dealt with memory."[64]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Betreutes Proggen | 15/15[65] |

| The Daily Campus | |

| Dead End Follies | 7.7/10[66] |

| Indie Style | |

| Pitchfork | 7.3/10 (Stage 1)[23] 7.9/10 (Stage 4)[39] |

| Resident Advisor | 4.3/5 (Stage 6)[44] |

| Sputnikmusic | |

| Tiny Mix Tapes | |

The first three stages of Everywhere at the End of Time were received with mild positivity from critics. Brian Howe from Pitchfork expressed concern about whether the series would be romanticizing the concept of dementia, explaining his personal experience with the disease was "very little like a 'beautiful daydream.' In fact, there was nothing aesthetic about it."[23] As Andrew O'Keefe noticed, after the release of the first stage, "there was a dissatisfied, 'is that it?' from some critical corners," however adding "its establishment of character and memorable motifs are what grant power to every subsequent stage."[70] Pat Beane from Tiny Mix Tapes felt the first stage doesn't "conjure any specific memories," but rather "induces the feeling of remembering" itself, writing this is due to "the unsettling power of the Caretaker's cozying dissociative work."[22] However, Frank Falisi's review of Stage 2 stated the record is not a general depiction of the disease, but rather the Caretaker's process through it, adding the album is "a collage, a manipulation, a piece no more penetrating than an erudite sermon or a well-knead sonnet or the original gramophone 78s that backbone it."[29] Writing of Stage 3, Beach Sloth from Entropy called it the most intriguing of the first three stages, as it "avoids the desire to simply explore the pure physical decay of the compositions, differentiating it from William Basinski’s output;" however, further stating that this is due to the Caretaker opting for a "more direct, less intellectualized approach."[34]

The last three stages were more positively received by critics. Also writing for Pitchfork, Miles Bowe stated Stage 4 became much more empathetic, as it did not present the aestheticized style of the first stage, but rather "only confusion, terror, and tragedy," concluding the risk of "pale romanticization" was avoided here.[39] Andrew O'Keefe felt the Post-Awareness stages were more difficult to approach critically, as they "provoke an immediate, personal reaction that is unique to each listener."[38] James Catchpole stated Stage 4 presents the "pleasurable memories disguis[ing] a trembling, existential terror and the caverns of deepening isolation,"[71] while Sam Goldner stated Stage 4 is the most "immersive, unsettling album" by the Caretaker since An Empty Bliss Beyond This World;[40] however, Frank Falisi suggested Stage 5, "then, is the loop unspooling (endlessly) off the capstans and piling up until new shapes form."[72] On his review of Stage 6, Andrew Ryce described the long length of the project as lending it "a unique force," adding Everywhere at the End of Time makes an attempt at "blurring the boundary between music and sound art."[44]

The complete edition of Everywhere at the End of Time received further praise from music critics. Except for Stage 3, Tiny Mix Tapes reviewed each album individually and gave the "EUREKA!" award to Stages 1, 4, and 6, writing they "defy categorization and explore the constructed boundaries between 'music' and 'noise,'" further adding each one of them is "worthy of careful consideration."[22][40][46] Writing for DGN Omega, Julia Szostak stated Everywhere at the End of Time does "a remarkable job at taking us on an emotional journey through the stages of dementia," later adding Kirby had "more than succeeded" on doing so.[73] Holly Hazelwood stated Everywhere at the End of Time is a record that "sticks with you," due to its melodies being "haunting and infecting."[15] Esther Ju from The Daily Campus stated the record received "immense critical acclaim, not for making it to the Billboard Hot 100, but for its poetic approach to a human side effect of real life," concluding that the series' ability to spread "its awareness through the evocative portrayal of its outcome" makes "chronic memory loss a spoken about topic."[19]

There was also criticism drew to Everywhere at the End of Time. Writing for Varsity, Sidney Franklyn stated the record "suffers in its reliance on our morbid fascination at human mortality, without any of its underlying humanity," further adding its final five minutes "demonstrates the commitment to aesthetics over realism," opining that the series still finds itself more interested in the destruction of the Caretaker persona, rather than the pain that accompanies "real" human destruction.[74] Writing of the first Post-Awareness stage, Winesburgohio from Sputnikmusic felt "the more obviously unsettling one [Kirby] renders their music, the less haunting and affecting it is," stating the album tried to be affecting and failed in doing so; the reviewer added that the reaction was due to three main reasons: the first one being that the listener "can feel the creator beyond the music, pulling the strings, desperate to elicit a desired reaction," the second one being Kirby's previous records were disorienting in ways difficult to locate, whereas Stage 4 is "a landscape of post-apocalyptic drones and cheesy radio interjections," and the third one being that Stage 4 focuses only on personal memory, whereas the Caretaker's previous releases combined the concept with cultural memory.[68]

Internet phenomenon

After the release of the sixth stage, the complete edition of Everywhere at the End of Time received highly positive reception from Internet users, with user review aggregators Rate Your Music and Sputnik Music registering ratings of 4.3 and 4.5 respectively; the series became further popularized by various YouTube videos considering it disturbing throughout 2019 and 2020.[75] It later inspired others to re-create the record using other themes or mental disorders, with albums such as Nowhere at the Millenium of Space recreating the record with music from the 1960s to the 1980s, or the fan-made "schizophrenia" edition recreating it as a depiction of the stages of schizophrenia.[76] The most famous attempt at creating a Caretaker fan-made album is Memories Overlooked, a hundred-track album where a large number of vaporwave musicians paid tribute to the Caretaker; it was later revealed that all of the digital proceeds from the album would be donated to the Alzheimer's Association.[77] There is also a small fanbase of Everywhere at the End of Time entirely dedicated to find every sample Kirby used when producing the record, including the Post-Awareness stages.[49]

In October 2020, the series gained further attention from TikTok users, who challenged each other to listen to the work in full due to its long length.[78] This has triggered some negative backlash from other users, who felt the album being turned into a test of endurance could possibly offend dementia patients and their relatives. However, on an interview with The New York Times, Kirby stated the record being turned into an online challenge is "a reaction to a need for experiences and shared experiences which goes hand in hand with modern social media tropes," adding anything that might raise awareness about Alzheimer's and dementia is a good thing, "especially among the young."[79] The official YouTube upload of the album by Kirby has accumulated over 10 million views as of April 2021.[80]

Joseph Earp from Junkee stated the bigger problem were fictional stories about the album being shared on the platform, such as claims that the record can be used to make dementia patients remember.[81] Various creepypasta-like stories have been invented on the internet in regards to the series, with some of the TikTok users stating the record causes its listeners to experience symptoms of dementia themselves.[49] Meaghan Garvey from NPR hypothesized this might have been due to a video uploaded by YouTuber A Bucked Of Jake titling Everywhere at the End of Time "the darkest album I have ever heard," with a thumbnail presenting the stylised phrase "THIS ALBUM WILL BREAK YOU;" however, Garvey further opposed the backlash to these kinds of comments, stating these reactions are not surprising due to introductions to experimental music often causing disturbing effects on its listeners.[82]

When asked by Patrick Clarke from The Quietus if he had noticed his record gained attention on social media, Kirby stated its official YouTube upload view rate had been increasing exponentially, adding the record being turned into a TikTok challenge would also be good for him, as "the hardest thing for any independent work to attain is its visibility."[83] The complete edition of the series has also been partially turned into a meme, with several images on Know Your Meme presenting their writers forgetting what they were going to say.[75][84] On a year-end report listing of music popularized by TikTok presented by the Variety magazine, Everywhere at the End of Time was included in the section "Unexpected Hits and Niche Discoveries," whereby "TikTok's community helped shape internet and IRL culture with these unearthed gems."[85] Brian Browne, the president of Dementia Care Education, concluded Kirby "really was onto something in terms of being able to — through the medium of music — lead a younger generation on a journey through the sounds of what the brain is going through, through a dementing process," adding the record is "a much welcome thing, because it produces the empathy that’s needed."[79]

Track listing

All track listings and lengths adapted from Bandcamp.[16]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "A1 - It's just a burning memory" | 3:32 |

| 2. | "A2 - We don't have many days" | 3:30 |

| 3. | "A3 - Late afternoon drifting" | 3:35 |

| 4. | "A4 - Childishly fresh eyes" | 2:58 |

| 5. | "A5 - Slightly Bewildered" | 2:01 |

| 6. | "A6 - Things that are beautiful and transient" | 4:34 |

| 7. | "B1 - All that follows is true" | 3:31 |

| 8. | "B2 - An autumnal equinox" | 2:46 |

| 9. | "B3 - Quiet internal rebellions" | 3:30 (Bandcamp) 3:33 (YouTube) |

| 10. | "B4 - The loves of my entire life" | 4:04 |

| 11. | "B5 - Into each others eyes" | 4:36 |

| 12. | "B6 - My heart will stop in joy" | 2:41 |

| Total length: | 41:31 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "C1 - A losing battle is raging" | 4:37 |

| 2. | "C2 - Misplaced in time" | 4:42 |

| 3. | "C3 - What does it matter how my heart breaks" | 2:37 |

| 4. | "C4 - Glimpses of hope in trying times" | 4:43 |

| 5. | "C5 - Surrendering to despair" | 5:03 |

| 6. | "D1 - I still feel as though I am me" | 4:07 |

| 7. | "D2 - Quiet dusk coming early" | 3:36 |

| 8. | "D3 - Last moments of pure recall" | 3:52 |

| 9. | "D4 - Denial unravelling" | 4:16 |

| 10. | "D5 - The way ahead feels lonely" | 4:15 |

| Total length: | 41:55 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "E1 - Back there Benjamin" | 4:14 |

| 2. | "E2 - And heart breaks" | 4:05 |

| 3. | "E3 - Hidden sea buried deep" | 1:20 |

| 4. | "E4 - Libet's all joyful camaraderie" | 3:12 |

| 5. | "E5 - To the minimal great hidden" | 1:41 |

| 6. | "E6 - Sublime beyond loss" | 2:10 |

| 7. | "E7 - Bewildered in other eyes" | 1:51 |

| 8. | "E8 - Long term dusk glimpses" | 3:33 |

| 9. | "F1 - Gradations of arms length" | 1:31 |

| 10. | "F2 - Drifting time misplaced" | 4:15 |

| 11. | "F3 - Internal bewildered world" | 3:29 |

| 12. | "F4 - Burning despair does ache" | 2:37 |

| 13. | "F5 - Aching cavern without lucidity" | 1:19 |

| 14. | "F6 - An empty bliss beyond this world" | 3:36 |

| 15. | "F7 - Libet delay" | 3:57 |

| 16. | "F8 - Mournful cameraderie" | 2:39 |

| Total length: | 45:36 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "G1 - Stage 4 Post-Awareness Confusions" | 22:09 |

| 2. | "H1 - Stage 4 Post-Awareness Confusions" | 21:53 |

| 3. | "I1 - Stage 4 Temporary Bliss State" | 21:01 |

| 4. | "J1 - Stage 4 Post-Awareness Confusions" | 22:16 |

| Total length: | 1:27:21 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "K1 - Stage 5 Advanced plaque entanglements" | 22:35 |

| 2. | "L1 - Stage 5 Advanced plaque entanglements" | 22:48 |

| 3. | "M1 - Stage 5 Synapse retrogenesis" | 20:48 |

| 4. | "N1- Stage 5 Sudden time regression into isolation" | 22:08 |

| Total length: | 1:28:21 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "O1 - Stage 6 A confusion so thick you forget forgetting" | 21:52 |

| 2. | "P1 - Stage 6 A brutal bliss beyond this empty defeat" | 21:36 |

| 3. | "Q1 - Stage 6 Long decline is over" | 21:09 |

| 4. | "R1 - Stage 6 Place in the World fades away" (Contains 1:00 of silence) | 21:19 |

| Total length: | 1:25:58 | |

References

- Melfi, Daniel (7 October 2019). "Leyland James Kirby On The Caretaker, Alzheimer's Disease And His Show At Unsound Festival". Electronic Beats. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- "Selected Memories from the Haunted Ballroom". Brainwashed. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- O'Neal, Seal (31 October 2013). "A scene from The Shining inspired a haunting ode to dying memory". AV Club. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- McKeating, Scott (3 January 2006). "The Caretaker - Theoretically Pure Anterograde Amnesia - Review". Stylus Magazine. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- "Persistent Repetition Of Phrases". Forced Exposure. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- "The Caretaker: Persistent Repetition of Phrases". Fact. 26 August 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Powell, Mike (14 June 211). "The Caretaker: An Empty Bliss Beyond This World Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- "The 50 Best Ambient Albums of All Time". Pitchfork. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Davenport, Joe (28 June 2011). "James Kirby (The Caretaker)". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Parks, Andrew (17 October 2016). "Leyland Kirby on The Caretaker's New Project: Six Albums Exploring Dementia". Bandcamp Daily. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- Dunn, Parker (26 September 2020). "'Everywhere at the End of Time' Depicts the Horrors of Dementia Through Sound". The Daily Utah Chronicle. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Bates, Landon (18 September 2018). "The Process: The Caretaker". The Believer. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Bazin, Alexandre (9 May 2018). "The Caretaker_PRESENCES électronique 2018". YouTube. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Doran, John (22 September 2016). "Out Of Time: Leyland James Kirby And The Death Of A Caretaker". The Quietus. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Hazelwood, Holly (18 January 2021). "Rediscover: The Caretaker: Everywhere at the End of Time". Spectrum Culture. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Caretaker, The (22 September 2016). "Everywhere at the end of time". Bandcamp. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Mark Lore, Adrian (17 November 2017). "Where are they now? Where aren't they yet? Catching up with Leyland Kirby". The Observer. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Caretaker, The (21 September 2016). "Everywhere At The End Of Time - Stage 1". Boomkat. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Ju, Esther (22 February 2021). "Casual Cadenza: 'Everywhere at the End of Time'". The Daily Campus. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Barnett, Michael (7 April 2017). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End of Time: Stages I-II – Review". This Is Darkness. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Padua, Pat (23 January 2017). "The Caretaker: Everywhere at the End of Time". Spectrum Culture. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Beane, Pat. "The Caretaker - Everywhere at the end of time | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "The Caretaker: Everywhere at the End of Time". Pitchfork. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "DOSSIER-PEDAGOGIQUE-Ivan-Seal-The-Caretaker.pdf" (PDF). FRAC Auvergne. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- Leahy, Sydney (16 February 2021). "Everywhere at The End of Time". The Blue & Gold. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Caretaker, The (5 April 2017). "Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stage 2". Boomkat. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Lelievre, Benoit. "Album Review : The Caretaker - Everywhere At The End of Time (2016)". Dead End Follies. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Caretaker, The (5 April 2017). "Everywhere At The End Of Time – Stage 2". Boomkat. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Music Review: The Caretaker - Everywhere at the end of time - Stage 2". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "Music / The Caretaker". TV Tropes. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- "8053_Dossier de presse The Caretaker-Ivan Seal - FRAC Auvergne.pdf" (PDF). FRAC Auvergne. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- Caretaker, The (27 September 2017). "Everywhere At The End Of Time - Stage 3". Boomkat. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- "8053_Dossier enseignant Ivan Seal.pdf" (PDF). FRAC Auvergne. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- Sloth, Beach (22 October 2017). "THE CARETAKER – EVERYWHERE AT THE END OF TIME – STAGE 3". Entropy. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Barnett, Michael (19 May 2018). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End of Time: Stages III & IV – Review". This Is Darkness. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Caretaker, The (14 March 2019). "Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 4-6 (4CD Set)". Boomkat. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Caretaker, The (5 April 2018). "Everywhere At The End Of Time - Stage 4". Boomkat. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- O'Keefe, Andrew (3 April 2019). "The Caretaker — Everywhere At The End Of Time (Stages 4-6)". No Wave. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- Bowe, Miles (26 April 2018). "The Caretaker - Everywhere at the End of Time - Stage 4 Album Review". Pirchfork. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Goldner, Sam (2018). "The Caretaker - Everywhere at the end of time - Stage 4 | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- Catchpole, James. "THE CARETAKER – EVERYWHERE AT THE END OF TIME – STAGE 5". Fluid Radio. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- Fitzgerald, James. "Brown wax home recording of Invicible eagle march, played on mandolin by James Fitzgerald". UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- Reisberg, Barry (1999). "Retrogenesis: clinical, physiologic, and pathologic mechanisms in brain aging, Alzheimer's and other dementing processes". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- Ryce, Andrew (12 April 2019). "The Caretaker - Everywhere At The End Of Time (Stage 6)". Resident Advisor. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- "The Echoes Of Anxiety: The Caretaker's Final Chapter". The Quietus. 14 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- Falisi, Frank. "The Caretaker - Everywhere at the end of time - Stage 6 | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Catchpole, James. "THE CARETAKER – EVERYWHERE AT THE END OF TIME: STAGE 6". Fluid Radio. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- Krusz, Layne (1 December 2020). "Place In The World Fades Away". YouTube. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- "Trivia / The Caretaker". TV Tropes. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Battaglia, Andy (14 November 2019). "In Abandoned 14th-Century Building in Poland, a Painting Show Where the Art Aims to Disappear". ARTnews. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Caretaker, The (13 March 2019). "Everywhere At The End Of Time - Stage 6". Boomkat. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Allen, Richard (3 June 2019). "Ivan Seal / The Caretaker ~ Everywhere at the end of time / everywhere, an empty bliss". A Closer Listen. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- Feiner, Benjamin (17 December 2020). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End of Time". Betreutes Proggen. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- "Google Translate". Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Sicilo (23 December 2020). "Everywhere At The End Of Time: storia di 6 album". CyberDude. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- "Google Translate". Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Rojo, Andrés (13 September 2019). "THE CARETAKER – EVERYWHERE AT THE END OF TIME (STAGES 1-6)". La Gramola de Keith. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- "Google Translate". Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- "IVAN SEAL / THE CARETAKER – Everywhere, an empty bliss". FRAC Auvergne. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "Google Translate". Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- "Fridge / The Caretaker". TV Tropes. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Strauss, Matthew (22 September 2016). "James Leyland Kirby Gives "The Caretaker" Alias Dementia, Releases First of Final 6 Albums". Pitchfork. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Andy (22 September 2016). "The Caretaker – Everywhere At The End Of Time". Raven Sings the Blues. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Darville, Jordan (22 September 2016). "This Musician Is Recreating Dementia's Progression Over Three Years With Six Albums". Fader. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Feiner, Benjamin (17 December 2020). "The Caretaker – Everywhere at the End of Time". Betreutes Proggen. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Lelievre, Benoit (15 September 2019). "Album Review : The Caretaker - Everywhere At The End of Time (2016)". Dead End Follies. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Verhasselt, Yannick (19 March 2019). "Het onvermijdelijk verstillende afscheid van The Caretaker op 'Everywhere at the end of time (stage 6)'". Indie Style. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Winesburgohio (12 April 2018). "Review: The Caretaker - Everywhere at the End of Time - Stage 4". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Falisi, Frank. "The Caretaker - Everywhere at the end of time - Stage 5 | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- O'Keefe, Andrew (24 March 2019). "The Caretaker — Everywhere At The End Of Time (Stages 1-3)". No Wave. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- Catchpole, James. "THE CARETAKER – EVERYWHERE AT THE END OF TIME: STAGE 4". Fluid Radio. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Falisi, Frank. "The Caretaker - Everywhere at the end of time - Stage 5 | Music Review". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- Szostak, Julia (15 March 2021). "Review: Everywhere at the End of Time". DGN Omega. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Franklyn, Sidney (16 July 2019). "Review: The Caretaker, Everywhere At The End Of Time Stages 1-6". Varsity. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "Everywhere at the End of Time". Know Your Meme. 16 October 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "Fan Works / The Caretaker". TV Tropes. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Bowe, Miles (5 October 2017). "Artists pay tribute to The Caretaker on 100-track charity compilation Memories Overlooked". Fact. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- Schroeder, Audra (19 October 2020). "TikTok turns The Caretaker's 6-hour song into a 'challenge'". Daily Dot. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Marcus, Ezra (23 October 2020). "Why Are TikTok Teens Listening to an Album About Dementia?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- vvmtest (14 March 2019). "The Caretaker - Everywhere At The End Of Time - Stages 1-6 (Complete)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Earp, Joseph (17 October 2020). "How An Obscure Six-Hour Ambient Record Is Terrifying A New Generation On TikTok". Junkee. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Garvey, Meaghan (22 October 2020). "What Happens When TikTok Looks To The Avant-Garde For A Challenge?". NPR. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Clarke, Patrick (19 October 2020). "'Everywhere At The End Of Time' Becomes TikTok Challenge". The Quietus. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "Everywhere at the End of Time: Images". Know Your Meme. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Aswad, Jem (16 December 2020). "Inside TikTok's First Year-End Music Report". Variety. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

External links

- The Caretaker on Bandcamp

- The Caretaker - Everywhere At The End Of Time - Stages 1-6 (Complete) on YouTube