Aeroplankton

Aeroplankton (or aerial plankton) are tiny lifeforms that float and drift in the air, carried by the current of the wind; they are the atmospheric analogue to oceanic plankton.

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

Most of the living things that make up aeroplankton are very small to microscopic in size, and many can be difficult to identify because of their tiny size. Scientists can collect them for study in traps and sweep nets from aircraft, kites or balloons.[1]

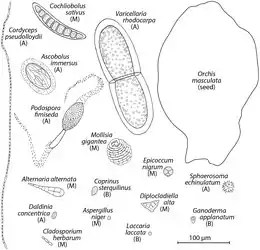

Aeroplankton is made up of numerous microbes, including viruses, about 1000 different species of bacteria, around 40,000 varieties of fungi, and hundreds of species of protists, algae, mosses and liverworts that live some part of their life cycle as aeroplankton, often as spores, pollen, and wind-scattered seeds. Additionally, peripatetic microorganisms are swept into the air from terrestrial dust storms, and an even larger amount of airborne marine microorganisms are propelled high into the atmosphere in sea spray. Aeroplankton deposits hundreds of millions of airborne viruses and tens of millions of bacteria every day on every square meter around the planet.

Overview

from common plants

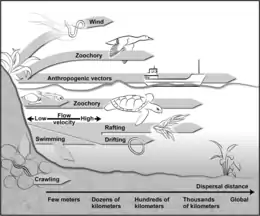

Dispersal is a vital component of an organism’s life-history,[7] and the potential for dispersal determines the distribution, abundance, and thus, the community dynamics of species at different sites.[8][9][10] A new habitat must first be reached before filters such as organismal abilities and adaptations, the quality of a habitat, and the established biological community determine the colonization efficiency of a species.[11] While larger animals can cover distances on their own and actively seek suitable habitats, small (<2 mm) organisms are often passively dispersed,[11] resulting in their more ubiquitous occurrence.[12] While active dispersal accounts for rather predictable distribution patterns, passive dispersal leads to a more randomized immigration of organisms.[8] Mechanisms for passive dispersal are the transport on (epizoochory) or in (endozoochory) larger animals (e.g., flying insects, birds, or mammals) and the erosion by wind.[11][13]

A propagule is any material that functions in propagating an organism to the next stage in its life cycle, such as by dispersal. The propagule is usually distinct in form from the parent organism. Propagules are produced by plants (in the form of seeds or spores), fungi (in the form of spores), and bacteria (for example endospores or microbial cysts).[14] Often cited as important requirement for effective wind dispersal is the presence of propagules (e.g., resting eggs, cysts, ephippia, juvenile and adult resting stages),[11][15][16] which also enables organisms to survive unfavorable environmental conditions until they enter a suitable habitat. These dispersal units can be blown from surfaces such as soil, moss, and the desiccated sediments of temporal waters. The passively dispersed organisms are typically pioneer colonizers.[17][18][19][13]

However, wind-drifted species vary in their vagility (probability to be transported with the wind),[20] with the weight and form of the propagules, and therefore, the wind speed required for their transport,[21] determining the dispersal distance. For example, in nematodes resting eggs are less effectively transported by wind than other life stages,[22] while organisms in anhydrobiosis are lighter and thus more readily transported than hydrated forms.[23][24] Because different organisms are, for the most part, not dispersed over the same distances, source habitats are also important, with the number of organisms contained in air declining with increasing distance from the source system.[17][25] The distances covered by small animals range from a few meters,[25] to several hundred meters,[17] and up to several kilometers.[22] While the wind dispersal of aquatic organisms is possible even during the wet phase of a transiently aquatic habitat,[11] during the dry stages a larger number of dormant propagules are exposed to wind and thus dispersed.[16][25][26] Freshwater organisms that must "cross the dry ocean" [11] to enter new aquatic island systems will be passively dispersed more successfully than terrestrial taxa.[11] However, numerous taxa from both soil and freshwater systems have been captured from the air (e.g., bacteria, several algae, ciliates, flagellates, rotifers, crustaceans, mites, and tardigrades).[17][25][26][27] While these have been qualitatively well studied, accurate estimates of their dispersal rates are lacking.[13]

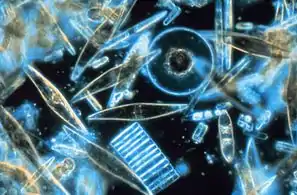

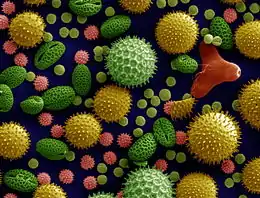

Pollen grains

Recent drilling cores from Switzerland have evidenced the oldest known fossils from flowering plants, pollen grains, which have revealed that flowering plants are 240-million-year-old.[28] Effective pollen dispersal is vital for maintenance of genetic diversity and fundamental for connectivity between spatially separated populations.[29] An efficient transfer of the pollen guarantees successful reproduction in flowering plants. No matter how pollen is dispersed, the male-female recognition is possible by mutual contact of stigma and pollen surfaces. Cytochemical reactions are responsible for pollen binding to a specific stigma.[30][2]

Allergic diseases are considered to be one of the most important contemporary public health problems affecting up to 15–35% of humans worldwide.[31] There is a body of evidence suggesting that allergic reactions induced by pollen are on the increase, particularly in highly industrial countries.[31][32][2]

Fungal spores

A wealth of correlative evidence suggests asthma is associated with fungi and triggered by elevated numbers of fungal spores in the environment.[33] Intriguing are reports of thunderstorm asthma. In a now classic study from the United Kingdom, an outbreak of acute asthma was linked to increases in Didymella exitialis ascospores and Sporobolomyces basidiospores associated with a severe weather event.[34] Thunderstorms are associated with spore plumes: when spore concentrations increase dramatically over a short period of time, for example from 20,000 spores/m3 to over 170,000 spores/m3 in 2 hours.[35] However, other sources consider pollen or pollution as causes of thunderstorm asthma.[36] Transoceanic and transcontinental dust events move large numbers of spores across vast distances and have the potential to impact public health,[37] and similar correlative evidence links dust blown off the Sahara with pediatric emergency room admissions on the island of Trinidad.[38][3]

The study of fungal spores in aeroplankton is called aeromycology.

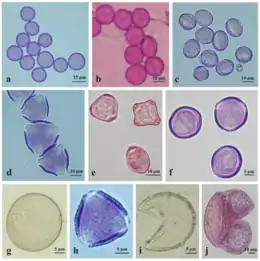

Fern spores

Pteridophyte spores, such as fern spores, similarly to pollen grains and fungal spores, are also components of aeroplankton.[39][40] Fungal spores usually rank first among bioaerosol constituents due to their highest concentrations (1000–10 000 m−3), while pollen grains and fern spores can reach a similar content (10–100 m−3).[41][32]

Arthropods

Many small animals, mainly arthropods (such as insects and spiders), are also carried upwards into the atmosphere by air currents and may be found floating several thousand feet up. Aphids, for example, are frequently found at high altitudes.

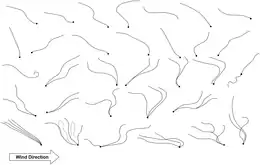

Ballooning, sometimes called kiting, is a process by which spiders, and some other small invertebrates, move through the air by releasing one or more gossamer threads to catch the wind, causing them to become airborne at the mercy of air currents.[42][43] A spider (usually limited to individuals of a small species), or spiderling after hatching,[44] will climb as high as it can, stand on raised legs with its abdomen pointed upwards ("tiptoeing"),[45] and then release several silk threads from its spinnerets into the air. These automatically form a triangular shaped parachute[46] which carries the spider away on updrafts of winds where even the slightest of breezes will disperse the arachnid.[45][46] The flexibility of their silk draglines can aid the aerodynamics of their flight, causing the spiders to drift an unpredictable and sometimes long distance.[47] Even atmospheric samples collected from balloons at five kilometres altitude and ships mid-ocean have reported spider landings. Mortality is high.[48]

The Earth's static electric field may also provide lift in windless conditions.[49]

Nematodes

Nematodes (roundworms), the most common animal taxon, are also found among aeroplankton.[16][17][25] Nematodes are an essential trophic link between unicellular organisms like bacteria, and larger organisms such as tardigrades, copepods, flatworms, and fishes.[13] For nematodes, anhydrobiosis is a widespread strategy allowing them to survive unfavorable conditions for months and even years.[50][51] Accordingly, nematodes can be readily dispersed by wind. However, as reported by Vanschoenwinkel et al.,[25] nematodes account for only about one percent of wind-drifted animals. Among the habitats colonized by nematodes are those that are strongly exposed to wind erosion as e.g., the shorelines of permanent waters, soils, mosses, dead wood, and tree bark.[52][13] In addition, within a few days of forming temporary waters such as phytotelmata were shown to be colonized by numerous nematode species.[19][53][13]

Marine microorganisms

A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes.[54] Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet.[55][56]

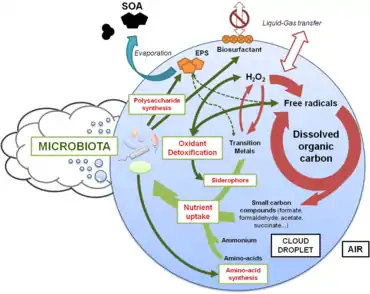

Microbial activity and clouds

Based on coordinated metagenomics/metatranscriptomics

The outdoor atmosphere harbors diverse microbial assemblages composed of bacteria, fungi and viruses [58] whose functioning remains largely unexplored.[57] While the occasional presence of human pathogens or opportunists can cause potential hazard,[59][60] in general the vast majority of airborne microbes originate from natural environments like soil or plants, with large spatial and temporal variations of biomass and biodiversity.[61][62] Once ripped off and aerosolized from surfaces by mechanical disturbances such as those generated by wind, raindrop impacts or water bubbling,[63][64] microbial cells are transported upward by turbulent fluxes.[65] They remain aloft for an average of ~3 days,[66] a time long enough for being transported across oceans and continents [67][68][69] until being finally deposited, eventually helped by water condensation and precipitation processes; microbial aerosols themselves can contribute to form clouds and trigger precipitation by serving as cloud condensation nuclei [70] and ice nuclei.[71][72][57]

Living airborne microorganisms may end up concretizing aerial dispersion by colonizing their new habitat,[73] provided that they survive their journey from emission to deposition. Bacterial survival is indeed naturally impaired during atmospheric transport,[74][75] but a fraction remains viable.[76][77] At high altitude, the peculiar environments offered by cloud droplets are thus regarded in some aspects as temporary microbial habitats, providing water and nutrients to airborne living cells.[78][79][80] In addition, the detection of low levels of heterotrophy [81] raises questions about microbial functioning in cloud water and its potential influence on the chemical reactivity of these complex and dynamic environments.[80][82] The metabolic functioning of microbial cells in clouds is still albeit unknown, while fundamental for apprehending microbial life conditions during long distance aerial transport and their geochemical and ecological impacts.[57]

New generation technologies

Over the last few years, next generation DNA sequencing technologies, such as metabarcoding as well as coordinated metagenomics and metatranscriptomics studies, have been providing new insights into microbial ecosystem functioning and the relationships that microorganisms maintain with their environment. There have been studies in soils,[83] the ocean,[84][85] the human gut [86] and elsewhere.[87][88] In the atmosphere, though, microbial gene expression and metabolic functioning remain largely unexplored, in part due to low biomass and sampling difficulties.[57] So far, metagenomics has confirmed high fungal, bacterial and viral biodiversity,[89][90][91][92] and targeted genomics and transcriptomics towards ribosomal genes has supported earlier findings about the maintenance of metabolic activity in aerosols [93][94] and in clouds.[62] In atmospheric chambers airborne bacteria have been consistently demonstrated to react to the presence of a carbon substrate by regulating ribosomal gene expressions.[95][57]

Gallery

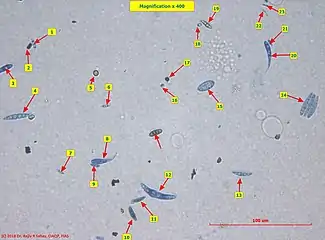

Pteridophyta spores, including fern spores, in the air of Lublin

Pteridophyta spores, including fern spores, in the air of Lublin Airborne fungal spores

Airborne fungal spores.JPG.webp) Detail of the formation of a dense aeroplankton cloud at sunset, over the Loire river in France

Detail of the formation of a dense aeroplankton cloud at sunset, over the Loire river in France

See also

- Aeolian processes

- Aerobiology

- Biological dispersal

- Dispersal vector

- Seed dispersal

- Organisms at high altitude

References

- A. C. Hardy and P. S. Milne (1938) Studies in the Distribution of Insects by Aerial Currents. Journal of Animal Ecology, 7(2):199-229

- Denisow, B. and Weryszko-Chmielewska, E. (2015) "Pollen grains as airborne allergenic particles". Acta Agrobotanica, 68(4). doi:10.5586/aa.2015.045.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Pringle, A. (2013) "Asthma and the diversity of fungal spores in air". PLoS Pathogens, 9(6): e1003371. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003371.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Figure adapted from: Ingold CT (1971) Fungal spores: their liberation and dispersal, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Cho, M., Neubauer, P., Fahrenson, C. and Rechenberg, I. (2018) "An observational study of ballooning in large spiders: Nanoscale multifibers enable large spiders’ soaring flight". PLoS biology, 16(6): e2004405. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2004405.g007.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Ptatscheck, Christoph; Traunspurger, Walter (2020). "The ability to get everywhere: Dispersal modes of free-living, aquatic nematodes". Hydrobiologia. 847 (17): 3519–3547. doi:10.1007/s10750-020-04373-0. S2CID 221110776.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Bonte, Dries; Dahirel, Maxime (2017). "Dispersal: A central and independent trait in life history". Oikos. 126 (4): 472–479. doi:10.1111/oik.03801.

- Rundle, Simon D.; Robertson, Anne L.; Schmid-Araya, Jenny M. (2002). Freshwater Meiofauna: Biology and Ecology. ISBN 9789057821097.

- Kneitel, Jamie M.; Miller, Thomas E. (2003). "Dispersal Rates Affect Species Composition in Metacommunities of Sarracenia purpurea Inquilines". The American Naturalist. 162 (2): 165–171. doi:10.1086/376585. PMID 12858261. S2CID 17576931.

- Cottenie, Karl (2005). "Integrating environmental and spatial processes in ecological community dynamics". Ecology Letters. 8 (11): 1175–1182. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00820.x. PMID 21352441.

- Incagnone, Giulia; Marrone, Federico; Barone, Rossella; Robba, Lavinia; Naselli-Flores, Luigi (2015). "How do freshwater organisms cross the "dry ocean"? A review on passive dispersal and colonization processes with a special focus on temporary ponds". Hydrobiologia. 750: 103–123. doi:10.1007/s10750-014-2110-3. hdl:10447/101976. S2CID 13892871.

- Finlay, B. J. (2002). "Global Dispersal of Free-Living Microbial Eukaryote Species". Science. 296 (5570): 1061–1063. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1061F. doi:10.1126/science.1070710. PMID 12004115. S2CID 19508548.

- Ptatscheck, Christoph; Gansfort, Birgit; Traunspurger, Walter (2018). "The extent of wind-mediated dispersal of small metazoans, focusing nematodes". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 6814. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.6814P. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-24747-8. PMC 5931521. PMID 29717144.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - T.Y. Chuang and W.H. Ko. 1981. Propagule size: Its relation to population density of microorganisms in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 13(3).

- Panov, Vadim E.; Krylov, Piotr I.; Riccardi, Nicoletta (2004). "Role of diapause in dispersal and invasion success by aquatic invertebrates". Journal of Limnology. 63: 56. doi:10.4081/jlimnol.2004.s1.56.

- Nkem, Johnson N.; Wall, Diana H.; Virginia, Ross A.; Barrett, John E.; Broos, Emma J.; Porazinska, Dorota L.; Adams, Byron J. (2006). "Wind dispersal of soil invertebrates in the Mc Murdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica". Polar Biology. 29 (4): 346–352. doi:10.1007/s00300-005-0061-x. S2CID 32516212.

- Maguire, Bassett (1963). "The Passive Dispersal of Small Aquatic Organisms and Their Colonization of Isolated Bodies of Water". Ecological Monographs. 33 (2): 161–185. doi:10.2307/1948560. JSTOR 1948560.

- Ptatscheck, Chistoph; Traunspurger, Walter (2014). "The meiofauna of artificial water-filled tree holes: Colonization and bottom-up effects". Aquatic Ecology. 48 (3): 285–295. doi:10.1007/s10452-014-9483-2. S2CID 15256569.

- Cáceres, Carla E.; Soluk, Daniel A. (2002). "Blowing in the wind: A field test of overland dispersal and colonization by aquatic invertebrates". Oecologia. 131 (3): 402–408. Bibcode:2002Oecol.131..402C. doi:10.1007/s00442-002-0897-5. PMID 28547712. S2CID 9941895.

- Jenkins, David G. (1995). "Dispersal-limited zooplankton distribution and community composition in new ponds". Hydrobiologia. 313–314: 15–20. doi:10.1007/BF00025926. S2CID 45667054.

- Parekh, Priya A.; Paetkau, Mark J.; Gosselin, Louis A. (2014). "Historical frequency of wind dispersal events and role of topography in the dispersal of anostracan cysts in a semi-arid environment". Hydrobiologia. 740: 51–59. doi:10.1007/s10750-014-1936-z. S2CID 18458173.

- Carroll, J.J. and Viglierchio, D.R. (1981). "On the transport of nematodes by the wind". Journal of Nematology, 13(4): 476.

- Van Gundy, Seymour D. (1965). "Factors in Survival of Nematodes". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 3: 43–68. doi:10.1146/annurev.py.03.090165.000355.

- Ricci, C.; Caprioli, M. (2005). "Anhydrobiosis in Bdelloid Species, Populations and Individuals". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 45 (5): 759–763. doi:10.1093/icb/45.5.759. PMID 21676827. S2CID 42270008.

- Vanschoenwinkel, Bram; Gielen, Saïdja; Seaman, Maitland; Brendonck, Luc (2008). "Any way the wind blows - frequent wind dispersal drives species sorting in ephemeral aquatic communities". Oikos. 117: 125–134. doi:10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16349.x.

- Vanschoenwinkel, Bram; Gielen, Saïdja; Vandewaerde, Hanne; Seaman, Maitland; Brendonck, Luc (2008). "Relative importance of different dispersal vectors for small aquatic invertebrates in a rock pool metacommunity". Ecography. 31 (5): 567–577. doi:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2008.05442.x.

- "X. The distribution of micro-organisms in air". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 40 (242–245): 509–526. 1886. doi:10.1098/rspl.1886.0077. S2CID 129825037.

- Feist-Burkhardt, Susanne; Hochuli, Peter A. (2013). "Angiosperm-like pollen and Afropollis from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of the Germanic Basin (Northern Switzerland)". Frontiers in Plant Science. 4: 344. doi:10.3389/fpls.2013.00344. PMC 3788615. PMID 24106492.

- Fénart, Stéphane; Austerlitz, Frédéric; Cuguen, Joël; Arnaud, Jean-François (2007). "Long distance pollen-mediated gene flow at a landscape level: The weed beet as a case study". Molecular Ecology. 16 (18): 3801–3813. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03448.x. PMID 17850547. S2CID 6382777.

- Edlund, A. F.; Swanson, R.; Preuss, D. (2004). "Pollen and Stigma Structure and Function: The Role of Diversity in Pollination". The Plant Cell Online. 16: S84–S97. doi:10.1105/tpc.015800. PMC 2643401. PMID 15075396.

- World Allergy Organization (WAO) White Book on Allergy. 2011. ISBN 9780615461823.

- Cecchi, Lorenzo (2013). "Introduction". Allergenic Pollen. pp. 1–7. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4881-1_1. ISBN 978-94-007-4880-4.

- Denning, D.W., O'driscoll, B.R., Hogaboam, C.M., Bowyer, P. and Niven, R.M. (2006) "The link between fungi and severe asthma: a summary of the evidence". European Respiratory Journal, 27(3): 615–626. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00074705.

- Packe, G.E. and Ayres, J. (1985) "Asthma outbreak during a thunderstorm". The Lancet, 326(8448): 199–204. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91510-7.

- Burch, M. and Levetin, E., 2002. Effects of meteorological conditions on spore plumes. International journal of biometeorology, 46(3), pp.107–117. doi:10.1007/s00484-002-0127-1.

- Bernstein, J.A., Alexis, N., Barnes, C., Bernstein, I.L., Nel, A., Peden, D., Diaz-Sanchez, D., Tarlo, S.M. and Williams, P.B., 2004. Health effects of air pollution. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 114(5), pp.1116-1123. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.030.

- Kellogg CA, Griffin DW (2006) "Aerobiology and the global transport of desert dust". Trends Ecol Evol, 21: 638–644. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.004.

- Gyan, K., Henry, W., Lacaille, S., Laloo, A., Lamsee-Ebanks, C., McKay, S., Antoine, R.M. and Monteil, M.A. (2005) "African dust clouds are associated with increased paediatric asthma accident and emergency admissions on the Caribbean island of Trinidad". International Journal of Biometeorology, 49(6): 371–376. doi:10.1007/s00484-005-0257-3.

- Burge, Harriet A.; Rogers, Christine A. (2000). "Outdoor Allergens". Environmental Health Perspectives. 108: 653–659. doi:10.2307/3454401. JSTOR 3454401. PMC 1637672. PMID 10931783. S2CID 16407560.

- Weryszko-Chmielewska, E. (2007). "Zakres badań i znaczenie aerobiologii". Aerobiologia. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Akademii Rolniczej, pages 6-10 (in Polish).

- Després, Vivianer.; Huffman, J.Alex; Burrows, Susannah M.; Hoose, Corinna; Safatov, Aleksandrs.; Buryak, Galina; Fröhlich-Nowoisky, Janine; Elbert, Wolfgang; Andreae, Meinrato.; Pöschl, Ulrich; Jaenicke, Ruprecht (2012). "Primary biological aerosol particles in the atmosphere: A review". Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology. 64 (1): 15598. Bibcode:2012TellB..6415598D. doi:10.3402/tellusb.v64i0.15598. S2CID 98741728.

- Heinrichs, Ann (2004). Spiders. Compass Point Books. ISBN 9780756505905. OCLC 54027960.

- Valerio, C.E. (1977). "Population structure in the spider Achaearranea Tepidariorum (Aranae, Theridiidae)". Journal of Arachnology. 3 (3): 185–190. JSTOR 3704941.

- Bond, Jason Edward (22 September 1999). Systematics and Evolution of the Californian Trapdoor Spider Genus Aptostichus Simon (Araneae: Mygalomorphae: Euctenizidae) (Thesis). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.691.8754. hdl:10919/29114.

- Weyman, G.S. (1995). "Laboratory studies of the factors stimulating ballooning behavior by Linyphiid spiders (Araneae, Linyphiidae)". Journal of Arachnology. 23 (2): 75–84. JSTOR 3705494.

- Schneider, J.M.; Roos, J.; Lubin, Y.; Henschel, J.R. (October 2001). "Dispersal of Stegodyphus Dumicola (Araneae, Eresidae): They do balloon after all!". Journal of Arachnology. 29 (1): 114–116. doi:10.1636/0161-8202(2001)029[0114:DOSDAE]2.0.CO;2.

- "Leap forward for 'flying' spiders". BBC News. 12 July 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Morley, Erica L.; Robert, Daniel (July 2018). "Electric Fields Elicit Ballooning in Spiders". Current Biology. 28 (14): 2324–2330.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.057. PMC 6065530. PMID 29983315.

- Gorham, Peter (Sep 2013). "Ballooning spiders: The case for electrostatic flight". arXiv:1309.4731 [physics.bio-ph].

- Hendriksen, N. B. (1982) "Anhydrobiosis in nematodes: studies on Plectus sp." In: New trends in soil biology (Eds: Lebrun, P. André, H. M., De Medts, A., Grégoire-Wibo, C. Wauthy, G.) pages 387–394, Louvain-la-Neurve, Belgium.

- Watanabe, M. (2006). "Anhydrobiosis in invertebrates". Applied Entomology and Zoology, 41(1): 15–31. doi:10.1303/aez.2006.15.

- Andrássy, I. (2009) "Free-living nematodes of Hungary III (Nematoda errantia)". Pedozoologica Hungarica No. 5. Hungarian Natural History Museum and Systematic Zoology, Research Group of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- Ptatscheck, Christoph; Dümmer, Birgit; Traunspurger, Walter (2015). "Nematode colonisation of artificial water-filled tree holes". Nematology. 17 (8): 911–921. doi:10.1163/15685411-00002913.

- Living Bacteria Are Riding Earth’s Air Currents Smithsonian Magazine, 11 January 2016.

- Robbins, Jim (13 April 2018). "Trillions Upon Trillions of Viruses Fall From the Sky Each Day". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Reche, Isabel; D’Orta, Gaetano; Mladenov, Natalie; Winget, Danielle M; Suttle, Curtis A (29 January 2018). "Deposition rates of viruses and bacteria above the atmospheric boundary layer". ISME Journal. 12 (4): 1154–1162. doi:10.1038/s41396-017-0042-4. PMC 5864199. PMID 29379178.

- Amato, Pierre; Besaury, Ludovic; Joly, Muriel; Penaud, Benjamin; Deguillaume, Laurent; Delort, Anne-Marie (2019). "Metatranscriptomic exploration of microbial functioning in clouds". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 4383. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.4383A. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41032-4. PMC 6416334. PMID 30867542.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Amato, P.; Brisebois, E.; Draghi, M.; Duchaine, C.; Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Huffman, J.A.; Mainelis, G.; Robine, E.; Thibaudon, M. (2017). "Main Biological Aerosols, Specificities, Abundance, and Diversity". Microbiology of Aerosols. pp. 1–21. doi:10.1002/9781119132318.ch1a. ISBN 9781119132318.

- Brodie, E. L.; Desantis, T. Z.; Parker, J. P. M.; Zubietta, I. X.; Piceno, Y. M.; Andersen, G. L. (2007). "Urban aerosols harbor diverse and dynamic bacterial populations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (1): 299–304. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104..299B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608255104. PMC 1713168. PMID 17182744.

- Courault, D.; Albert, I.; Perelle, S.; Fraisse, A.; Renault, P.; Salemkour, A.; Amato, P. (2017). "Assessment and risk modeling of airborne enteric viruses emitted from wastewater reused for irrigation". Science of the Total Environment. 592: 512–526. Bibcode:2017ScTEn.592..512C. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.105. PMID 28320526.

- Bowers, Robert M.; McLetchie, Shawna; Knight, Rob; Fierer, Noah (2011). "Spatial variability in airborne bacterial communities across land-use types and their relationship to the bacterial communities of potential source environments". The ISME Journal. 5 (4): 601–612. doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.167. PMC 3105744. PMID 21048802.

- Amato, Pierre; Joly, Muriel; Besaury, Ludovic; Oudart, Anne; Taib, Najwa; Moné, Anne I.; Deguillaume, Laurent; Delort, Anne-Marie; Debroas, Didier (2017). "Active microorganisms thrive among extremely diverse communities in cloud water". PLOS ONE. 12 (8): e0182869. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1282869A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182869. PMC 5549752. PMID 28792539.

- Aller, Josephine Y.; Kuznetsova, Marina R.; Jahns, Christopher J.; Kemp, Paul F. (2005). "The sea surface microlayer as a source of viral and bacterial enrichment in marine aerosols". Journal of Aerosol Science. 36 (5–6): 801–812. Bibcode:2005JAerS..36..801A. doi:10.1016/j.jaerosci.2004.10.012.

- Joung, Young Soo; Ge, Zhifei; Buie, Cullen R. (2017). "Bioaerosol generation by raindrops on soil". Nature Communications. 8: 14668. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814668J. doi:10.1038/ncomms14668. PMC 5344306. PMID 28267145.

- Carotenuto, Federico; Georgiadis, Teodoro; Gioli, Beniamino; Leyronas, Christel; Morris, Cindy E.; Nardino, Marianna; Wohlfahrt, Georg; Miglietta, Franco (2017). "Measurements and modeling of surface–atmosphere exchange of microorganisms in Mediterranean grassland". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 17 (24): 14919–14936. Bibcode:2017ACP....1714919C. doi:10.5194/acp-17-14919-2017.

- Burrows, S. M.; Butler, T.; Jöckel, P.; Tost, H.; Kerkweg, A.; Pöschl, U.; Lawrence, M. G. (2009). "Bacteria in the global atmosphere – Part 2: Modeling of emissions and transport between different ecosystems". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 9 (23): 9281–9297. Bibcode:2009ACP.....9.9281B. doi:10.5194/acp-9-9281-2009.

- Griffin, D.W.; Gonzalez-Martin, C.; Hoose, C.; Smith, D.J. (2017). "Global-Scale Atmospheric Dispersion of Microorganisms". Microbiology of Aerosols. pp. 155–194. doi:10.1002/9781119132318.ch2c. ISBN 9781119132318.

- Šantl-Temkiv, Tina; Gosewinkel, Ulrich; Starnawski, Piotr; Lever, Mark; Finster, Kai (2018). "Aeolian dispersal of bacteria in southwest Greenland: Their sources, abundance, diversity and physiological states". FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 94 (4). doi:10.1093/femsec/fiy031. PMID 29481623.

- Barberán, Albert; Ladau, Joshua; Leff, Jonathan W.; Pollard, Katherine S.; Menninger, Holly L.; Dunn, Robert R.; Fierer, Noah (2015). "Continental-scale distributions of dust-associated bacteria and fungi". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (18): 5756–5761. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5756B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420815112. PMC 4426398. PMID 25902536.

- Bauer, Heidi; Giebl, Heinrich; Hitzenberger, Regina; Kasper-Giebl, Anne; Reischl, Georg; Zibuschka, Franziska; Puxbaum, Hans (2003). "Airborne bacteria as cloud condensation nuclei". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 108 (D21): 4658. Bibcode:2003JGRD..108.4658B. doi:10.1029/2003JD003545.

- Morris, C. E.; Georgakopoulos, D. G.; Sands, D. C. (2004). "Ice nucleation active bacteria and their potential role in precipitation". Journal de Physique IV (Proceedings). 121: 87–103. doi:10.1051/jp4:2004121004.

- Creamean, J. M.; Suski, K. J.; Rosenfeld, D.; Cazorla, A.; Demott, P. J.; Sullivan, R. C.; White, A. B.; Ralph, F. M.; Minnis, P.; Comstock, J. M.; Tomlinson, J. M.; Prather, K. A. (2013). "Dust and Biological Aerosols from the Sahara and Asia Influence Precipitation in the Western U.S.". Science. 339 (6127): 1572–1578. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1572C. doi:10.1126/science.1227279. PMID 23449996. S2CID 2276891.

- Morris, C.E.; Sands, D.C. (2017). "Impacts of Microbial Aerosols on Natural and Agro-ecosystems: Immigration, Invasions, and their Consequences". Microbiology of Aerosols. pp. 269–279. doi:10.1002/9781119132318.ch4b. ISBN 9781119132318.

- Smith, David J.; Griffin, Dale W.; McPeters, Richard D.; Ward, Peter D.; Schuerger, Andrew C. (2011). "Microbial survival in the stratosphere and implications for global dispersal". Aerobiologia. 27 (4): 319–332. doi:10.1007/s10453-011-9203-5. S2CID 52107037.

- Amato, P.; Joly, M.; Schaupp, C.; Attard, E.; Möhler, O.; Morris, C. E.; Brunet, Y.; Delort, A.-M. (2015). "Survival and ice nucleation activity of bacteria as aerosols in a cloud simulation chamber". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 15 (11): 6455–6465. Bibcode:2015ACP....15.6455A. doi:10.5194/acp-15-6455-2015.

- Hill, Kimberly A.; Shepson, Paul B.; Galbavy, Edward S.; Anastasio, Cort; Kourtev, Peter S.; Konopka, Allan; Stirm, Brian H. (2007). "Processing of atmospheric nitrogen by clouds above a forest environment". Journal of Geophysical Research. 112 (D11): D11301. Bibcode:2007JGRD..11211301H. doi:10.1029/2006JD008002.

- Hara, Kazutaka; Zhang, Daizhou (2012). "Bacterial abundance and viability in long-range transported dust". Atmospheric Environment. 47: 20–25. Bibcode:2012AtmEn..47...20H. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.11.050.

- Temkiv, Tina Šantl; Finster, Kai; Hansen, Bjarne Munk; Nielsen, Niels Woetmann; Karlson, Ulrich Gosewinkel (2012). "The microbial diversity of a storm cloud as assessed by hailstones". FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 81 (3): 684–695. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01402.x. PMID 22537388.

- Fuzzi, Sandro; Mandrioli, Paolo; Perfetto, Antonio (1997). "Fog droplets—an atmospheric source of secondary biological aerosol particles". Atmospheric Environment. 31 (2): 287–290. Bibcode:1997AtmEn..31..287F. doi:10.1016/1352-2310(96)00160-4.

- Amato, P.; Demeer, F.; Melaouhi, A.; Fontanella, S.; Martin-Biesse, A.-S.; Sancelme, M.; Laj, P.; Delort, A.-M. (2007). "A fate for organic acids, formaldehyde and methanol in cloud water: Their biotransformation by micro-organisms". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 7 (15): 4159–4169. Bibcode:2007ACP.....7.4159A. doi:10.5194/acp-7-4159-2007.

- Sattler, Birgit; Puxbaum, Hans; Psenner, Roland (2001). "Bacterial growth in supercooled cloud droplets". Geophysical Research Letters. 28 (2): 239–242. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28..239S. doi:10.1029/2000GL011684.

- Vaitilingom, M.; Deguillaume, L.; Vinatier, V.; Sancelme, M.; Amato, P.; Chaumerliac, N.; Delort, A.-M. (2013). "Potential impact of microbial activity on the oxidant capacity and organic carbon budget in clouds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (2): 559–564. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110..559V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205743110. PMC 3545818. PMID 23263871.

- Baldrian, Petr; Kolařík, Miroslav; Štursová, Martina; Kopecký, Jan; Valášková, Vendula; Větrovský, Tomáš; Žifčáková, Lucia; Šnajdr, Jaroslav; Rídl, Jakub; Vlček, Čestmír; Voříšková, Jana (2012). "Active and total microbial communities in forest soil are largely different and highly stratified during decomposition". The ISME Journal. 6 (2): 248–258. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.95. PMC 3260513. PMID 21776033.

- Gifford, Scott M.; Sharma, Shalabh; Rinta-Kanto, Johanna M.; Moran, Mary Ann (2011). "Quantitative analysis of a deeply sequenced marine microbial metatranscriptome". The ISME Journal. 5 (3): 461–472. doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.141. PMC 3105723. PMID 20844569.

- Gilbert, Jack A.; Field, Dawn; Huang, Ying; Edwards, Rob; Li, Weizhong; Gilna, Paul; Joint, Ian (2008). "Detection of Large Numbers of Novel Sequences in the Metatranscriptomes of Complex Marine Microbial Communities". PLOS ONE. 3 (8): e3042. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3042G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003042. PMC 2518522. PMID 18725995.

- Franzosa, E. A.; Morgan, X. C.; Segata, N.; Waldron, L.; Reyes, J.; Earl, A. M.; Giannoukos, G.; Boylan, M. R.; Ciulla, D.; Gevers, D.; Izard, J.; Garrett, W. S.; Chan, A. T.; Huttenhower, C. (2014). "Relating the metatranscriptome and metagenome of the human gut". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (22): E2329–E2338. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E2329F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319284111. PMC 4050606. PMID 24843156.

- Satinsky, Brandon M.; Zielinski, Brian L.; Doherty, Mary; Smith, Christa B.; Sharma, Shalabh; Paul, John H.; Crump, Byron C.; Moran, Mary (2014). "The Amazon continuum dataset: Quantitative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic inventories of the Amazon River plume, June 2010". Microbiome. 2: 17. doi:10.1186/2049-2618-2-17. PMC 4039049. PMID 24883185.

- Chen, Lin-Xing; Hu, Min; Huang, Li-nan; Hua, Zheng-Shuang; Kuang, Jia-Liang; Li, Sheng-jin; Shu, Wen-Sheng (2015). "Comparative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses of microbial communities in acid mine drainage". The ISME Journal. 9 (7): 1579–1592. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.245. PMC 4478699. PMID 25535937.

- Be, Nicholas A.; Thissen, James B.; Fofanov, Viacheslav Y.; Allen, Jonathan E.; Rojas, Mark; Golovko, George; Fofanov, Yuriy; Koshinsky, Heather; Jaing, Crystal J. (2015). "Metagenomic Analysis of the Airborne Environment in Urban Spaces". Microbial Ecology. 69 (2): 346–355. doi:10.1007/s00248-014-0517-z. PMC 4312561. PMID 25351142.

- Whon, T. W.; Kim, M.-S.; Roh, S. W.; Shin, N.-R.; Lee, H.-W.; Bae, J.-W. (2012). "Metagenomic Characterization of Airborne Viral DNA Diversity in the Near-Surface Atmosphere". Journal of Virology. 86 (15): 8221–8231. doi:10.1128/JVI.00293-12. PMC 3421691. PMID 22623790.

- Yooseph, Shibu; Andrews-Pfannkoch, Cynthia; Tenney, Aaron; McQuaid, Jeff; Williamson, Shannon; Thiagarajan, Mathangi; Brami, Daniel; Zeigler-Allen, Lisa; Hoffman, Jeff; Goll, Johannes B.; Fadrosh, Douglas; Glass, John; Adams, Mark D.; Friedman, Robert; Venter, J. Craig (2013). "A Metagenomic Framework for the Study of Airborne Microbial Communities". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e81862. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...881862Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081862. PMC 3859506. PMID 24349140.

- Xu, Caihong; Wei, Min; Chen, Jianmin; Sui, Xiao; Zhu, Chao; Li, Jiarong; Zheng, Lulu; Sui, Guodong; Li, Weijun; Wang, Wenxing; Zhang, Qingzhu; Mellouki, Abdelwahid (2017). "Investigation of diverse bacteria in cloud water at Mt. Tai, China" (PDF). Science of the Total Environment. 580: 258–265. Bibcode:2017ScTEn.580..258X. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.081. PMID 28011017.

- Klein, Ann M.; Bohannan, Brendan J. M.; Jaffe, Daniel A.; Levin, David A.; Green, Jessica L. (2016). "Molecular Evidence for Metabolically Active Bacteria in the Atmosphere". Frontiers in Microbiology. 7: 772. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00772. PMC 4878314. PMID 27252689.

- Womack, A. M.; Artaxo, P. E.; Ishida, F. Y.; Mueller, R. C.; Saleska, S. R.; Wiedemann, K. T.; Bohannan, B. J. M.; Green, J. L. (2015). "Characterization of active and total fungal communities in the atmosphere over the Amazon rainforest". Biogeosciences. 12 (21): 6337–6349. Bibcode:2015BGeo...12.6337W. doi:10.5194/bg-12-6337-2015.

- Krumins, Valdis; Mainelis, Gediminas; Kerkhof, Lee J.; Fennell, Donna E. (2014). "Substrate-Dependent rRNA Production in an Airborne Bacterium". Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 1 (9): 376–381. doi:10.1021/ez500245y.