Pleuromutilin

Pleuromutilin and its derivatives are antibacterial drugs that inhibit protein synthesis in bacteria by binding to the peptidyl transferase component of the 50S subunit of ribosomes.[1]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

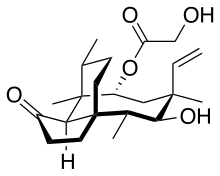

| Preferred IUPAC name

(3aS,4R,5S,6S,8R,9R,9aR,10R)-6-Ethenyl-5-hydroxy-4,6,9,10-tetramethyl-1-oxodecahydro-3a,9-propanocyclopenta[8]annulen-8-yl hydroxyacetate | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

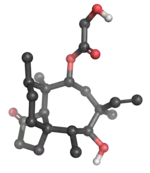

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.316 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C22H34O5 |

| Molar mass | 378.509 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

This class of antibiotics includes the licensed drugs lefamulin (for systemic use in humans), retapamulin (approved for topical use in humans), valnemulin and tiamulin (approved for use in animals) and the investigational drug azamulin.

History

Pleuromutilin was discovered as an antibiotic in 1950.[2] It is derived from the fungus Clitopilus passeckerianus (formerly Pleurotus passeckerianus), and has also been found in Drosophila subatrata, Clitopilus scyphoides, and some other Clitopilus species.[3]

References

- Maffioli, Sonia Ilaria (2013). "A chemist's survey of different antibiotic classes". In Gualerzi, Claudio O.; Brandi, Letizia; Fabbretti, Attilio; Pon, Cynthia L. (eds.). Antibiotics: Targets, Mechanisms and Resistance. Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–22. doi:10.1002/9783527659685.ch1. ISBN 978-3-527-65968-5. S2CID 11479628.

- Novak, R.; Shlaes, D. M. (2010). "The pleuromutilin antibiotics: A new class for human use". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 11 (2): 182–191. PMID 20112168. S2CID 41588014.

- Kilaru, Sreedhar; Collins, Catherine M.; Hartley, Amanda J.; Bailey, Andy M.; Foster, Gary D. (2009). "Establishing molecular tools for genetic manipulation of the pleuromutilin-producing fungus Clitopilus passeckerianus". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 75 (22): 7196–7204. doi:10.1128/AEM.01151-09. PMC 2786515. PMID 19767458. S2CID 22127410.

- Gibbons, E. Grant (1982). "Total synthesis of (±)-pleuromutilin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 104 (6): 1767–1769. doi:10.1021/ja00370a067. S2CID 102155530.

- Boeckman, Robert K.; Springer, Dane M.; Alessi, Thomas R. (1989). "Synthetic studies directed toward naturally occurring cyclooctanoids. 2. A stereocontrolled assembly of (±)-pleuromutilin via a remarkable sterically demanding oxy-Cope rearrangement". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 111 (21): 8284–8286. doi:10.1021/ja00203a043. S2CID 96627402.

- Fazakerley, Neal J.; Helm, Matthew D.; Procter, David J. (2013). "Total synthesis of (+)-pleuromutilin". Chemistry—A European Journal. 19 (21): 6718–6723. doi:10.1002/chem.201300968. PMID 23589420. S2CID 46105984.

- Murphy, Stephen K.; Zeng, Mingshuo; Herzon, Seth B. (2017). "A modular and enantioselective synthesis of the pleuromutilin antibiotics". Science. 356 (6341): 956–959. doi:10.1126/science.aan0003. PMC 7001679. PMID 28572392. S2CID 206658420.

Further reading

- Long, Katherine S.; Hansen, Lykke H.; Jakobsen, Lene; Vester, Birte (2006). "Interaction of pleuromutilin derivatives with the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 50 (4): 1458–1462. doi:10.1128/AAC.50.4.1458-1462.2006. PMC 1426994. PMID 16569865. S2CID 8900413.

- Lolk, Line; Pøhlsgaard, Jacob; Jepsen, Anne Sofie; Hansen, Lykke H.; Nielsen, Henrik; Steffansen, Signe I.; Sparving, Laura; Nielsen, Annette B.; Vester, Birte; Nielsen, Poul (2008). "A click chemistry approach to pleuromutilin conjugates with nucleosides or acyclic nucleoside derivatives and their binding to the bacterial ribosome". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 51 (16): 4957–4967. doi:10.1021/jm800261u. PMID 18680270. S2CID 931146.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.