Variants of SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has many variants; some are believed or have been believed to be of particular importance due to their potential for increased transmissibility, increased virulence, and reduced effectiveness of vaccines against them.[1][2] This article discusses such notable variants of SARS-CoV-2 and notable missense mutations found in these variants.

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The sequence WIV04/2019, belonging to the GISAID S clade / PANGO A lineage / Nextstrain 19B clade, is thought to most closely reflect the sequence of the original virus infecting humans known as "sequence zero", and is widely used as a reference sequence.[3]

Overview

There are many lineages of SARS-CoV-2.[4] The following table presents information and level of risk for variants with elevated or possibly elevated risk at present[5][6][7][8] or in the past. The intervals assume a 95% confidence or credibility level, unless otherwise stated.

| First detection | PANGOLIN lineage |

Nextstrain clade |

PHE variant |

Other names | Notable mutations | Evidence of clinical changes |

Spread | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locations | Date |

Transmissibility | Virulence | Antigenicity | ||||||

| Jan 2020 |

B.1.1.7 | 20I/501Y.V1 | VOC-20DEC-01 |

— | N501Y, 69–70del, P681H |

≈74% higher |

≈64% (32–104%) more lethal |

No evidence of change |

Global | |

| Mar 2020 |

B.1.1.207 | — | — | — | P681H |

No evidence of change |

No evidence of change |

— | International | |

| June 2020 |

B.1.429, B.1.427 |

20C/S:452R | — | CAL.20C |

I4205V, D1183Y, S13I, W152C, L452R | ≈20% (18.6–24.2%) higher |

≈827.5% (525–1130%) more lethal |

Moderate-to-significantly reduced neutralisation |

International | |

| Sep 2020 |

Not registered | Cluster 5, ΔFVI-spike |

Y453F, 69–70deltaHV |

— | — | Moderately decreased sensitivity to neutralising antibodies |

Likely extinct | |||

| Oct 2020 |

B.1.351 | 20H/501Y.V2 | VOC-20DEC-02 | 501Y.V2 |

N501Y, K417N, E484K |

≈50% (20–113%) higher |

No evidence of change |

Reduced neutralisation by antibodies |

International | |

| Dec 2020 |

P.1 | 20J/501Y.V3 | VOC-21JAN-02 | B.1.1.28.1 |

N501Y, E484K, K417T |

≈260% (240–280%) higher |

≈45% (50% CrI, 10–80%) more lethal |

Overall reduction in effective neutralisation |

International | |

| Dec 2020 |

B.1.525 | 20C |

VUI-21FEB-03 |

— | E484K, F888L |

Under investigation | Under investigation | Possibly reduced neutralisation |

International | |

- The naming format was updated in March 2021, changing the year from 4 to 2 digits and the month from 2 digits to a 3-letter abbreviation. For example, VOC-202101-02 became VOC-21JAN-02.[6]

- "—" denotes that no reliable sources could be found to cite.

- B.1.1.7 with E484K is separately designated VOC-21FEB-02

- Another preliminary study[27] has estimated that P.1 may be 140–220% more transmissible, with a credible interval with a low probability of 50%.

- The reported credible interval has a low probability of only 50%, so the estimated lethality can only be understood as possible, not certain nor likely.

- Includes B.1.525 and B.1.526.[5]

- Formerly UK1188.

Nomenclature

| PANGO lineages[31] | Notes to PANGO lineages[32] | Nextstrain clades,[33] 2021[34] | GISAID clades | Notable variants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.1–A.6 | 19B | S | contains "reference sequence" WIV04/2019[3] | |

| B.3–B.7, B.9, B.10, B.13–B.16 | 19A | L | ||

| O[lower-alpha 1] | ||||

| B.2 | V | |||

| B.1 | B.1.5–B.1.72 | 20A | G | Lineage B.1 in the PANGO Lineages nomenclature system |

| B.1.9, B.1.13, B.1.22, B.1.26, B.1.37 | GH | |||

| B.1.3–B.1.66 | 20C | Includes Lineage B.1.429 / CAL.20C[35] and Lineage B.1.525[5] | ||

| 20G | Predominant in US generally, Jan '21[35] | |||

| 20H | Includes B.1.351 aka 20H/501Y.V2 or 501.V2 lineage | |||

| B.1.1 | 20B | GR | Includes B.1.1.207 | |

| 20D | ||||

| 20J | Includes P.1 and P.2[36][37] | |||

| 20F | ||||

| 20I | Includes lineage B.1.1.7 aka VOC-202012/01, VOC-20DEC-01 or 20I/501Y.V1 | |||

| B.1.177 | 20E (EU1)[34] | GV[lower-alpha 1] | Derived from 20A[34] | |

No consistent nomenclature has been established for SARS-CoV-2.[39] Colloquially, including by governments and news organizations, concerning variants are often referred to by the country in which they were first identified,[40][41][42] but as of January 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) is working on "standard nomenclature for SARS-CoV-2 variants that does not reference a geographical location".[43]

While there are many thousands of variants of SARS-CoV-2,[44] subtypes of the virus can be put into larger groupings such as lineages or clades.[lower-alpha 2] Three main, generally used nomenclatures[39] have been proposed:

- As of January 2021, GISAID—referring to SARS-CoV-2 as hCoV-19[32]—had identified eight global clades (S, O, L, V, G, GH, GR, and GV).[45]

- In 2017, Hadfield et al. announced Nextstrain, intended "for real-time tracking of pathogen evolution".[46] Nextstrain has later been used for tracking SARS-CoV-2, identifying 11 major clades[lower-alpha 3] (19A, 19B, and 20A–20I) as of January 2021.[33]

- In 2020, Rambaut et al. of the Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak Lineages (PANGOLIN)[47] software team proposed in an article[31] "a dynamic nomenclature for SARS-CoV-2 lineages that focuses on actively circulating virus lineages and those that spread to new locations";[39] as of February 2021, six major lineages (A, B, B.1, B.1.1, B.1.177, B.1.1.7) had been identified.[4][48]

Each national public health institute may also institute its own nomenclature system for the purposes of tracking specific variants. For example, Public Health England designated each tracked variant by year, month and number in the format [YYYY][MM]/[NN], prefixing 'VUI' or 'VOC' for a variant under investigation or a variant of concern respectively.[6] This system has now been modified and now uses the format [YY][MMM]-[NN], where the month is written out using a three-letter code.[6]

Criteria for notability

Viruses generally acquire mutations over time, giving rise to new variants. When a new variant appears to be growing in a population, it can be labeled as an "emerging variant".

Some of the potential consequences of emerging variants are the following:[10][49]

- Increased transmissibility

- Increased morbidity

- Increased mortality

- Ability to evade detection by diagnostic tests

- Decreased susceptibility to antiviral drugs (if and when such drugs are available)

- Decreased susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies, either therapeutic (e.g., convalescent plasma or monoclonal antibodies) or in laboratory experiments

- Ability to evade natural immunity (e.g., causing reinfections)

- Ability to infect vaccinated individuals

- Increased risk of particular conditions such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome or long-haul COVID.

- Increased affinity for particular demographic or clinical groups, such as children or immunocompromised individuals.

Variants that appear to meet one or more of these criteria may be labeled "variants under investigation" or "variants of interest" pending verification and validation of these properties. The primary characteristic of a variant of interest is that it shows evidence that demonstrates it is the cause of an increased proportion of cases or unique outbreak clusters; however, it must also have limited prevalence or expansion at national levels, or the classification would be elevated to a "variant of concern".[6][50] If there is clear evidence that the effectiveness of prevention or intervention measures for a particular variant is substantially reduced, that variant is termed a "variant of high consequence".[5]

Notable variants

Cluster 5

In early November 2020, Cluster 5, also referred to as ΔFVI-spike by the Danish State Serum Institute (SSI),[21] was discovered in Northern Jutland, Denmark, and is believed to have been spread from minks to humans via mink farms. On 4 November 2020, it was announced that the mink population in Denmark would be culled to prevent the possible spread of this mutation and reduce the risk of new mutations happening. A lockdown and travel restrictions were introduced in seven municipalities of Northern Jutland to prevent the mutation from spreading, which could compromise national or international responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. By 5 November 2020, some 214 mink-related human cases had been detected.[51]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that cluster 5 has a "moderately decreased sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies".[22] SSI warned that the mutation could reduce the effect of COVID-19 vaccines under development, although it was unlikely to render them useless. Following the lockdown and mass-testing, SSI announced on 19 November 2020 that cluster 5 in all probability had become extinct.[23] As of 1 February 2021, authors to a peer-reviewed paper, all of whom were from the SSI, assessed that cluster 5 was not in circulation in the human population.[52]

Lineage B.1.1.7 / Variant of Concern 20DEC-01

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

First detected in October 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom from a sample taken the previous month in Kent,[53] Lineage B.1.1.7,[54] was previously known as the first Variant Under Investigation in December 2020 (VUI – 202012/01)[55] and later notated as VOC-202012/01.[6] It is also known as lineage B.1.1.7 or 20I/501Y.V1 (formerly 20B/501Y.V1).[56][57][10] Since then, its prevalence odds have doubled every 6.5 days, the presumed generational interval.[58][59] It is correlated with a significant increase in the rate of COVID-19 infection in United Kingdom, associated partly with the N501Y mutation.[60] There is some evidence that this variant has 40%–80% increased transmissibility (with most estimates lying around the middle to higher end of this range),[61] and early analyses suggest an increase in lethality.[62][63]

Variant of Concern 21FEB-02

Variant of Concern 21FEB-02 (previously written as VOC-202102/02), described by Public Health England (PHE) as "B.1.1.7 with E484K"[6] is of the same lineage in the Rambaut classification system but has an additional E484K mutation. As of 17 March 2021, there are 39 confirmed cases of VOC-21FEB-02 in the UK.[6] On 4 March 2021, scientists reported B.1.1.7 with E484K mutations in the state of Oregon. In 13 test samples analysed, one had this combination, which appeared to have arisen spontaneously and locally, rather than being imported.[64][65][66]

Lineage B.1.1.207

First sequenced in August 2020 in Nigeria,[67] the implications for transmission and virulence are unclear but it has been listed as an emerging variant by the US Centers for Disease Control.[10] Sequenced by the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases in Nigeria, this variant has a P681H mutation, shared in common with UK's Lineage B.1.1.7. It shares no other mutations with Lineage B.1.1.7 and as of late December 2020 this variant accounts for around 1% of viral genomes sequenced in Nigeria, though this may rise.[67] By March 2021, Lineage B.1.1.207 had been detected in Peru, Germany, Singapore, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Costa Rica, South Korea, Canada, Australia, Japan, France, Italy, Ecuador, Mexico, UK and the USA.[15]

Lineage B.1.1.317

While B.1.1.317 is not considered a variant of concern, Queensland Health forced 2 people undertaking hotel quarantine in Brisbane, Australia to undergo an additional 5 days quarantine on top of the mandatory 14 days after it was confirmed they were infected with this variant.[68]

Lineage B.1.1.318

Lineage B.1.1.318 was designated by PHE as a VUI (VUI-21FEB-04,[6] previously VUI-202102/04) on 24 February 2021. 16 cases of it have been detected in the UK.[6][69]

Lineage B.1.351

On 18 December 2020, the 501.V2 variant, also known as 501.V2, 20H/501Y.V2 (formerly 20C/501Y.V2), VOC-20DEC-02 (formerly VOC-202012/02), or lineage B.1.351,[10] was first detected in South Africa and reported by the country's health department.[70] Researchers and officials reported that the prevalence of the variant was higher among young people with no underlying health conditions, and by comparison with other variants it is more frequently resulting in serious illness in those cases.[71][72] The South African health department also indicated that the variant may be driving the second wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in the country due to the variant spreading at a more rapid pace than other earlier variants of the virus.[70][71]

Scientists noted that the variant contains several mutations that allow it to attach more easily to human cells because of the following three mutations in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) in the spike glycoprotein of the virus: N501Y,[70][73] K417N, and E484K.[74][75] The N501Y mutation has also been detected in the United Kingdom.[70][76]

Lineage B.1.429 / CAL.20C

Lineage B.1.429, also known as CAL.20C, is defined by five distinct mutations (I4205V and D1183Y in the ORF1ab-gene, and S13I, W152C, L452R in the spike proteins S-gene), of which the L452R (previously also detected in other unrelated lineages) was of particular concern.[35][77] B.1.429 is possibly more transmissible, but further study is necessary to confirm this.[77] CDC has listed B.1.429 and the related B.1.427 as "variants of concern," and cites a preprint for saying that they exhibit a ~20% increase in viral transmissibility, have a "Significant impact on neutralization by some, but not all," therapeutics that have been given Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by FDA for treatment or prevention of COVID-19, and moderately reduce neutralization by plasma collected by people who have previously infected by the virus or who have received a vaccine against the virus.[78]

B.1.429 was first observed in July 2020 by researchers at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, California, in one of 1,230 virus samples collected in Los Angeles County since the start of the COVID-19 epidemic.[79] It was not detected again until September when it reappeared among samples in California, but numbers remained very low until November.[80][81] In November 2020, the CAL.20C variant accounted for 36 percent of samples collected at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and by January 2021, the CAL.20C variant accounted for 50 percent of samples.[77] In a joint press release by University of California, San Francisco, California Department of Public Health, and Santa Clara County Public Health Department,[82] the variant was also detected in multiple counties in Northern California. From November to December 2020, the frequency of the variant in sequenced cases from Northern California rose from 3% to 25%.[83] In a preprint, CAL.20C is described as belonging to clade 20C and contributing approximately 36% of samples, while an emerging variant from the 20G clade accounts for some 24% of the samples in a study focused on Southern California. Note however that in the US as a whole, the 20G clade predominates, as of January 2021.[35] Following the increasing numbers of CAL.20C in California, the variant has been detected at varying frequencies in most US states. Small numbers have been detected in other countries in North America, and in Europe, Asia and Australia.[80][81]

Lineage B.1.525

B.1.525, also called VUI-21FEB-03[6] (previously VUI-202102/03) by Public Health England (PHE) and formerly known as UK1188,[6] does not carry the same N501Y mutation found in B.1.1.7, 501.V2 and P.1, but carries the same E484K-mutation as found in the P.1, P.2, and 501.V2 variants, and also carries the same ΔH69/ΔV70 deletion (a deletion of the amino acids histidine and valine in positions 69 and 70) as found in B.1.1.7, N439K variant (B.1.141 and B.1.258) and Y453F variant (Cluster 5).[84] B.1.525 differs from all other variants by having both the E484K-mutation and a new F888L mutation (a substitution of phenylalanine (F) with leucine (L) in the S2 domain of the spike protein). As of March 5, it had been detected in 23 countries, including the UK, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Nigeria, Ghana, Jordan, Japan, Singapore, Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, Austria, Malaysia, Switzerland, the Republic of Ireland and the US.[85][86][87][29][88][89][90] It has also been reported in Mayotte, the overseas department/region of France.[85] The first cases were detected in December 2020 in the UK and Nigeria, and as of 15 February, it had occurred in the highest frequency among samples in the latter country.[29] As of 24 February, 56 cases were found in the UK.[6] Denmark, which sequence all their COVID-19 cases, found 113 cases of this variant from January 14 to February 21, of which seven were directly related to foreign travels to Nigeria.[86]

UK experts are studying it to understand how much of a risk it could be. It is currently regarded as a "variant under investigation", but pending further study, it may become a "variant of concern". Prof Ravi Gupta, from the University of Cambridge spoke to the BBC and said B.1.525 appeared to have "significant mutations" already seen in some of the other newer variants, which is partly reassuring as their likely effect is to some extent more predictable.[28]

Lineage P.1

Lineage P.1, termed Variant of Concern 21JAN-02[6] (formerly VOC-202101/02) by Public Health England[6] and 20J/501Y.V3 by Nextstrain,[5] was detected in Tokyo on 6 January 2021 by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID). The new lineage was first identified in four people who arrived in Tokyo having travelled from the Brazilian Amazonas state on 2 January 2021.[91] On 12 January 2021, the Brazil-UK CADDE Centre confirmed 13 local cases of the P.1 new lineage in the Amazon rain forest.[92] This variant of SARS-CoV-2 has been named P.1 lineage (although it is a descendant of B.1.1.28, the name B.1.1.28.1 is not permitted and thus the resultant name is P.1), and has 17 unique amino acid changes, 10 of which in its spike protein, including the three concerning mutations: N501Y, E484K and K417T.[92][93][94][95]

The new lineage was absent in samples collected from March to November 2020 in Manaus, Amazonas state, but it was detected for the same city in 42% of the samples from 15–23 December 2020, followed by 52.2% during 15–31 December and 85.4% during 1–9 January 2021.[92] A separate Brazilian study identified another sub-lineage of the B.1.1.28 lineage circulating in the state of Rio de Janeiro, now named P.2 lineage,[96] that harbours the E484K mutation but not the N501Y and K417T mutation.[97][98] The P.2 lineage evolved independently in Rio de Janeiro without being directly related to the P.1 lineage from Manaus.[92]

A study found that P.1 infections can produce nearly ten times more viral load compared to persons infected by one of the other Brazilian lineages (B.1.1.28 or B.1.195). P.1 also showed 2.2 times higher transmissibility with the same ability to infect both adults and older persons, suggesting P.1 lineages are more successful at infecting younger humans with no gender differential.[99]

A study of samples collected in Manaus between November 2020 and January 2021, indicated the P.1 lineage to be 1.4–2.2 times more transmissible and was shown to be capable of evading 25–61% of inherited immunity from previous coronavirus diseases, leading to the possibility of reinfection after recovery from an earlier COVID-19 infection. As for the fatality ratio, P.1 infections were also found to be 10–80% more lethal.[100][101][27]

A vaccine study found that Pfizer and Moderna fully vaccinated people have significantly decreased neutralization effect against P.1, meaning the vaccinated person would suffer a higher risk of getting a mild P.1 infection while however still being 100% protected against potential hospitalisation or death.[102]

Preliminary data from two studies indicate that the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine is effective against the P.1 variant, although the exact level of efficacy has not yet been released.[103][104] Preliminary data from a study conducted by Instituto Butantan suggest that CoronaVac is effective against the P.1 variant as well, and the study will be expanded to obtain definitive data.[105]

Lineage P.3

On 18 February 2021, the Department of Health of the Philippines confirmed the detection of two mutations of COVID-19 in Central Visayas after samples from patients were sent to undergo genome sequencing. The mutations were later named as E484K and N501Y, which were detected in 37 out of 50 samples, with both mutations co-occurrent in 29 out of these. There were no official names for the variants and the full sequence was yet to be identified.[106]

On 13 March, the Department of Health confirmed the mutations constitutes a variant which was designated as lineage P.3.[107] On the same day, it also confirmed the first Lineage P.1 COVID-19 case in the country. Although the P.1 and P.3 variants stem from the same lineage B.1.1.28, the department said that P.3 variant's impact on vaccine efficacy and transmissibility is yet to be ascertained. The Philippines had 98 cases of P.3 variant on 13 March.[108] On 12 March it was announced that P.3 had also been detected in Japan.[109][110] On 17 March, the United Kingdom confirmed its first two cases,[111] where PHE termed it VUI-21MAR-02.[6]

Notable missense mutations

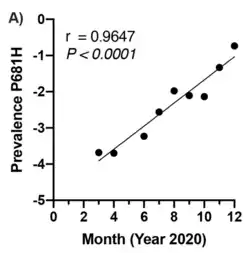

D614G

D614G is a missense mutation that affects the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. The frequency of this mutation in the viral population has increased during the pandemic. G (glycine) has replaced D (aspartic acid) at position 614 in many countries, especially in Europe though more slowly in China and the rest of East Asia, supporting the hypothesis that G increases the transmission rate, which is consistent with higher viral titers and infectivity in vitro.[3] Researchers with the PANGOLIN tool nicknamed this mutation "Doug".[113]

In July 2020, it was reported that the more infectious D614G SARS-CoV-2 variant had become the dominant form in the pandemic.[114][115][116][117] PHE confirmed that the D614G mutation had a "moderate effect on transmissibility" and was being tracked internationally.[118]

The global prevalence of D614G correlates with the prevalence of loss of smell (anosmia) as a symptom of COVID-19, possibly mediated by higher binding of the RBD to the ACE2 receptor or higher protein stability and hence higher infectivity of the olfactory epithelium.[119]

Variants containing the D614G mutation are found in the G clade by GISAID[3] and the B.1 clade by the PANGOLIN tool.[3]

E484K

The name of the mutation, E484K, refers to an exchange whereby the glutamic acid (E) is replaced by lysine (K) at position 484.[120] It is nicknamed "Eeek".[113]

E484K has been reported to be an escape mutation (i.e., a mutation that improves a virus's ability to evade the host's immune system[121][122]) from at least one form of monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2, indicating there may be a "possible change in antigenicity".[123] The P.1. lineage described in Japan and Manaus,[92] the P.2 lineage (also known as B.1.1.248 lineage, Brazil)[97] and 501.V2 (South Africa) exhibit this mutation.[123] A limited number of B.1.1.7 genomes with E484K mutation have also been detected.[124] Monoclonal and serum-derived antibodies are reported to be from 10 to 60 times less effective in neutralizing virus bearing the E484K mutation.[125][24] On 2 February 2021, medical scientists in the United Kingdom reported the detection of E484K in 11 samples (out of 214,000 samples), a mutation that may compromise current vaccine effectiveness.[126][127]

N501Y

N501Y denotes a change from asparagine (N) to tyrosine (Y) in amino-acid position 501.[118] N501Y has been nicknamed "Nelly".[113]

This change is believed by PHE to increase binding affinity because of its position inside the spike glycoprotein's receptor-binding domain, which binds ACE2 in human cells; data also support the hypothesis of increased binding affinity from this change.[11] Variants with N501Y include P.1 (Brazil/Japan),[123][92] Variant of Concern 20DEC-01 (UK), 501.V2 (South Africa), and COH.20G/501Y (Columbus, Ohio). This last became the dominant form of the virus in Columbus in late December 2020 and January and appears to have evolved independently of other variants.[128][129]

S477G/N

A highly flexible region in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2, starting from residue 475 and continuing up to residue 485, was identified using bioinformatics and statistical methods in several studies. The University of Graz[130] and the Biotech Company Innophore[131] have shown in a recent publication that structurally, the position S477 shows the highest flexibility among them.[132]

At the same time, S477 is hitherto the most frequently exchanged amino acid residue in the RBDs of SARS-CoV-2 mutants. By using molecular dynamics simulations of RBD during the binding process to hACE2, it has been shown that both S477G and S477N strengthen the binding of the SARS-COV-2 spike with the hACE2 receptor. The vaccine developer BioNTech[133] referenced this amino acid exchange as relevant regarding future vaccine design in a preprint published in February 2021.[134]

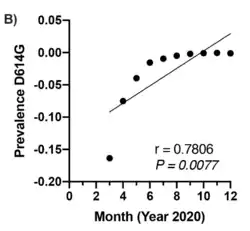

P681H

In January 2021, scientists reported in a preprint that the mutation 'P681H', a characteristic feature of the significant novel SARS-CoV-2 variants detected in the U.K. (B.1.1.7) and Nigeria (B.1.1.207), is showing a significant exponential increase in worldwide frequency, similar to the now globally prevalent 'D614G'.[135][112]

New variant detection and assessment

On 26 January 2021, the British government said it would share its genomic sequencing capabilities with other countries in order to increase the genomic sequencing rate and trace new variants, and announced a "New Variant Assessment Platform".[136] As of January 2021, more than half of all genomic sequencing of COVID-19 was carried out in the UK.[137]

Origin of variants

Researchers have suggested that multiple mutations can arise in the course of the persistent infection of an immunocompromised patient, particularly when the virus develops escape mutations under the selection pressure of antibody or convalescent plasma treatment,[138][139] with the same deletions in surface antigens repeatedly recurring in different patients.[140]

Differential vaccine effectiveness

The potential emergence of a SARS-CoV-2 variant that is moderately or fully resistant to the antibody response elicited by the current generation of COVID-19 vaccines may necessitate modification of the vaccines.[141] Trials indicate many vaccines developed for the initial strain have lower efficacy for some variants against symptomatic COVID-19.[142] As of February 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration believed that all FDA authorized vaccines remained effective in protecting against circulating strains of SARS-CoV-2.[141] Early results suggest protection to the UK variant from the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines.[143][144] One study indicated that the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine had an efficacy of 42–89% against the B.1.1.7 variant, versus 71–91% against non-B.1.1.7 variants.[145] Preliminary data from a clinical trial indicated that the Novavax vaccine was ~96% effective for symptoms against the original variant, ~86% against B.1.1.7, and ~60% against the "South African" B.1.351 variant.[146]

501.V2 variant

Moderna has launched a trial of a vaccine to tackle the South African 501.V2 variant (also known as B.1.351).[147] On 17 February 2021, Pfizer announced neutralization activity was reduced by two-thirds for the 501.V2 variant, while stating no claims about the efficacy of the vaccine in preventing illness for this variant could yet be made.[148] Decreased neutralizing activity of sera from patients vaccinated with Moderna and Pfizer vaccines against B.1.351 was latter confirmed by several studies.[144][149] On 1 April 2021, an update on a Pfizer/BioNTech South African vaccine trial stated that the vaccine was 100% effective so far (i.e., vaccinated participants saw no cases), with six of nine infections in the placebo control group being the B.1.351 variant.[150]

In January, Johnson & Johnson, which held trials for its Ad26.COV2.S vaccine in South Africa, reported the level of protection against moderate to severe COVID-19 infection was 72% in the United States and 57% in South Africa.[151]

On 6 February 2021, the Financial Times reported that provisional trial data from a study undertaken by South Africa's University of the Witwatersrand in conjunction with Oxford University demonstrated reduced efficacy of the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine against the 501.V2 variant.[152] The study found that in a sample size of 2,000 the AZD1222 vaccine afforded only "minimal protection" in all but the most severe cases of COVID-19.[153] On 7 February 2021, the Minister for Health for South Africa suspended the planned deployment of around 1 million doses of the vaccine whilst they examine the data and await advice on how to proceed.[154][155]

P1 variant

The P1 variant (also known as 20J/501Y.V3), initially identified in Brazil, seems to partially escape vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNtech vaccine.[149]See also

- RaTG13, the closest known relative to SARS-CoV-2

- Pandemic prevention § Surveillance and mapping

Notes

- In another source, GISAID name a set of 7 clades without the O clade but including a GV clade.[38]

- According to the WHO, "Lineages or clades can be defined based on viruses that share a phylogenetically determined common ancestor".[39]

- As of January 2021, at least one of the following criteria must be met in order to count as a clade in the Nextstrain system (quote from source):[lower-alpha 4]

- A clade reaches >20% global frequency for 2 or more months

- A clade reaches >30% regional frequency for 2 or more months

- A VOC (‘variant of concern’) is recognized (applies currently [6 January 2021] to 501Y.V1 and 501Y.V2)

References

- "Coronavirus variants and mutations: The science explained". BBC News. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Kupferschmidt, Kai (15 January 2021). "New coronavirus variants could cause more reinfections, require updated vaccines". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. doi:10.1126/science.abg6028. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Zhukova, Anna; Blassel, Luc; Lemoine, Frédéric; Morel, Marie; Voznica, Jakub; Gascuel, Olivier (24 November 2020). "Origin, evolution and global spread of SARS-CoV-2". Comptes Rendus Biologies: 1–20. doi:10.5802/crbiol.29. PMID 33274614.

- "Lineage descriptions". cov-lineages.org. Pango team.

- "SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions". cdc.org. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- "Variants: distribution of cases data". gov.uk. Government Digital Service.

- "Global Report Investigating Novel Coronavirus Haplotypes". cov-lineages.org. Pango team.

- "Living Evidence - SARS-CoV-2 variants". Agency for Clinical Innovation. nsw.gov.au. Ministry of Health (New South Wales). Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- "Nextstrain". nextstrain.org. Nextstrain.

- "Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants". cdc.org (Science brief). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Chand et al. (2020), p. 6, Potential impact of spike variant N501Y.

- Volz, Erik; Mishra, Swapnil; Chand, Meera; Barrett, Jeffrey; Johnson, Robert; Geidelberg, Lily; et al. (4 January 2021). Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B.1.1.7 in England: Insights from linking epidemiological and genetic data (Preprint). doi:10.1101/2020.12.30.20249034. hdl:10044/1/85239. Retrieved 22 March 2021 – via medRxiv.

- Challen, Robert; Brooks-Pollock, Ellen; Read, Jonathan; Dyson, Louise; Tsaneva-Atanasova, Krasimira; Danon, Leon (10 March 2021). "Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study". The BMJ. 372. doi:10.1136/bmj.n579. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 7941603. PMID 33687922. n579. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Risk related to the spread of new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the EU/EEA - first update (Risk assessment). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2 February 2021.

- "Lineage B.1.1.207". cov-lineages.org. Pango team. Retrieved 11 March 2021. Graphic shows B.1.1.207 detected in Peru, Germany, Singapore, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Costa Rica, South Korea, Canada, Australia, Japan, France, Italy, Ecuador, Mexico, UK and the USA.

- S, Sruthi (10 February 2021). "Notable Variants And Mutation Of SARS-CoV-2". BioTecNika. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- "Lineage B.1.429". cov-lineages.org. Pango team. Retrieved 19 March 2021. Graphic shows B.1.429 detected in the USA, Mexico, Canada, the UK, France, Denmark, Australia, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Guadeloupe, and Aruba.

- "Southern California COVID-19 Strain Rapidly Expands Global Reach". Cedars-Sinai Newsroom. Los Angeles. 11 February 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- Wadman, Meredith (23 February 2021). "California coronavirus strain may be more infectious - and lethal". Science News. doi:10.1126/science.abh2101. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- "SARS-CoV-2 mink-associated variant strain - Denmark". WHO Disease Outbreak News. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- Lassaunière, Ria; Fonager, Jannik; Rasmussen, Morten; Frische, Anders; Strandh, Charlotta; Rasmussen, Thomas; et al. (10 November 2020). SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations arising in Danish mink, their spread to humans and neutralization data (Preprint). Statens Serum Institut. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- "SARS-CoV-2 mink-associated variant strain – Denmark". World Health Organization. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- "De fleste restriktioner lempes i Nordjylland" [Most restrictions eased in North Jutland] (in Danish). Ministry of Health (Denmark). 19 November 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

Sekventeringen af de positive prøver viser samtidig, at der ikke er påvist yderligere tilfælde af minkvariant med cluster 5 siden den 15. september, hvorfor Statens Serums Institut vurderer, at denne variant med stor sandsynlighed er døet ud.

[At the same time, the sequencing of the positive samples shows that no further cases of mink variant with cluster 5 have been detected since 15 September, which is why the Statens Serums Institut assesses that this variant has most likely died out.] - Kupferschmidt, Kai (22 January 2021). "New mutations raise specter of 'immune escape'". Science. 371 (6527): 329–330. doi:10.1126/science.371.6527.329. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33479129. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "P.1". cov-lineages.org. Pango team. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Coutinho, Renato; Marquitti, Flavia; Ferreira, Leonardo; Borges, Marcelo; Silva, Rafael; Canton, Otavio; et al. (23 March 2021). "Model-based estimation of transmissibility and reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 P.1 variant" (Preprint). doi:10.1101/2021.03.03.21252706. Retrieved 8 April 2021 – via medRxiv. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Faria, Nuno; Mellan, Thomas; Whittaker, Charles; Claro, Ingra; Candido, Darlan; Mishra, Swapnil; et al. (3 March 2021). "Genomics and epidemiology of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil" (Preprint). doi:10.1101/2021.02.26.21252554. PMC 7941639. PMID 33688664. Retrieved 23 March 2021 – via medRxiv.

P.1 can be between 1.4-2.2 (50% BCI, with a 96% posterior probability of being >1) times more transmissible than local non-P1 lineages ... We estimate that infections are 1.1–1.8 (50% BCI, 81% posterior probability of being >1) times more likely to result in mortality in the period following P.1's emergence, compared to before, although posterior estimates of this relative risk are also correlated with inferred cross-immunity

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Roberts, Michelle (16 February 2021). "Another new coronavirus variant seen in the UK". BBC News. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "B.1.525". cov-lineages.org. Pango team. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- This table is an adaptation and expansion of Alm et al., figure 1.

- Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; O’Toole, Á.; et al. (2020). "A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology". Nature Microbiology. 5 (11): 1403–1407. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5. PMID 32669681. S2CID 220544096. Cited in Alm et al.

- Alm, E.; Broberg, E. K.; Connor, T.; Hodcroft, E. B.; Komissarov, A. B.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; et al. (2020). "Geographical and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 clades in the WHO European Region, January to June 2020". Euro Surveillance. 25 (32). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001410. PMC 7427299. PMID 32794443.

- "Nextclade" (What are the clades?). clades.nextstrain.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Bedford, Trevor; Hodcroft, Emma B; Neher, Richard A (6 January 2021). "Updated Nextstrain SARS-CoV-2 clade naming strategy". nextstrain.org/blog. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Zhang, Wenjuan; Davis, Brian D.; Chen, Stephanie S.; Martinez, Jorge M Sincuir; Plummer, Jasmine T.; Vail, Eric (2021). "Emergence of a novel SARS-CoV-2 strain in Southern California, USA". doi:10.1101/2021.01.18.21249786. S2CID 231646931. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "PANGO lineages-Lineage B.1.1.28". cov-lineages.org. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Variant: 20J/501Y.V3". covariants.org. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- "clade tree (from 'Clade and lineage nomenclature')". www.gisaid.org. 4 July 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- WHO Headquarters (8 January 2021). "3.6 Considerations for virus naming and nomenclature". SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequencing for public health goals: Interim guidance, 8 January 2021. World Health Organization. p. 6. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "Don't call it the 'British variant.' Use the correct name: B.1.1.7". STAT. 9 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- Flanagan, Ryan (2 February 2021). "Why the WHO won't call it the 'U.K. variant', and you shouldn't either". Coronavirus. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- For a list of sources using names referring to the country in which the variants were first identified, see, for example, Talk:South African COVID variant and Talk:U.K. Coronavirus variant.

- World Health Organization (15 January 2021). "Statement on the sixth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Koyama, Takahiko; Platt, Daniel; Parida, Laxmi (June 2020). "Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 98 (7): 495–504. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.253591. PMC 7375210. PMID 32742035.

We detected in total 65776 variants with 5775 distinct variants.

- "Global phylogeny, updated by Nextstrain". GISAID. 18 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Hadfield, James; Megill, Colin; Bell, Sidney; Huddleston, John; Potter, Barney; Callender, Charlton; Sagulenko, Pavel; Bedford, Trevor; Neher, Richard (22 May 2018). Kelso, Janet (ed.). "Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution". Bioinformatics. 34 (23): 4121–4123. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407. ISSN 1367-4803. PMC 6247931. PMID 29790939.

- "cov-lineages/pangolin: Software package for assigning SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences to global lineages". Github. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- "Addendum: A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology". Nature Microbiology. 15 July 2020. doi:10.1038/s41564-021-00872-5. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- Contributor, IDSA (2 February 2021). "COVID "Mega-variant" and eight criteria for a template to assess all variants". Science Speaks: Global ID News. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- Griffiths, Emma; Tanner, Jennifer; Knox, Natalie; Hsiao, Will; Van Domselaar, Gary (15 January 2021). "CanCOGeN Interim Recommendations for Naming, Identifying,and Reporting SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern" (PDF). CanCOGeN (nccid.ca). Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- "Detection of new SARS-CoV-2 variants related to mink" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Larsen, Helle Daugaard; Fonager, Jannik; Lomholt, Frederikke Kristensen; Dalby, Tine; Benedetti, Guido; Kristensen, Brian; Urth, Tinna Ravnholt; Rasmussen, Morten; Lassaunière, Ria; Rasmussen, Thomas Bruun; Strandbygaard, Bertel (4 February 2021). "Preliminary report of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in mink and mink farmers associated with community spread, Denmark, June to November 2020". Eurosurveillance. 26 (5). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.5.210009. ISSN 1025-496X. PMC 7863232. PMID 33541485.

- "Covid: Ireland, Italy, Belgium and Netherlands ban flights from UK". BBC News. 20 December 2020.

- Chand, Meera; Hopkins, Susan; Dabrera, Gavin; Achison, Christina; Barclay, Wendy; Ferguson, Neil; Volz, Erik; Loman, Nick; Rambaut, Andrew; Barrett, Jeff (21 December 2020). Investigation of novel SARS-COV-2 variant: Variant of Concern 202012/01 (PDF) (Report). Public Health England. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- "PHE investigating a novel strain of COVID-19". Public Health England (PHE). 14 December 2020.

- Rambaut, Andrew; Loman, Nick; Pybus, Oliver; Barclay, Wendy; Barrett, Jeff; Carabelli, Alesandro; Connor, Tom; Peacock, Tom; L. Robertson, David; Vol, Erik (2020). Preliminary genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in the UK defined by a novel set of spike mutations (Report). Written on behalf of COVID-19 Genomics Consortium UK. Retrieved 20 December 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kupferschmidt, Kai (20 December 2020). "Mutant coronavirus in the United Kingdom sets off alarms but its importance remains unclear". Science Mag. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "New evidence on VUI-202012/01 and review of the public health risk assessment". khub.net. 15 December 2020.

- "COG-UK Showcase Event - YouTube". YouTube. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- "New evidence on VUI-202012/01 and review of the public health risk assessment". Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Estimated transmissibility and severity of novel SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern 202012/01 in England". CMMID Repository. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021 – via GitHub.

Cited in European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (21 January 2021). "Risk related to the spread of new SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the EU/EEA – first update" (PDF). Stockholm: ECDC. p. 9. Retrieved 24 January 2021. - Gallagher, James (22 January 2021). "Coronavirus: UK variant 'may be more deadly'". BBC News. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Peter Horby, Catherine Huntley, Nick Davies, John Edmunds, Neil Ferguson, Graham Medley, Andrew Hayward, Muge Cevik, Calum Semple (11 February 2021). "NERVTAG paper on COVID-19 variant of concern B.1.1.7: NERVTAG update note on B.1.1.7 severity (2021-02-11)" (PDF). www.gov.uk.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mandavilli, Apoorva (5 March 2021). "In Oregon, Scientists Find a Virus Variant With a Worrying Mutation - In a single sample, geneticists discovered a version of the coronavirus first identified in Britain with a mutation originally reported in South Africa". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Chen, Rita E.; et al. (4 March 2021). "Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies". Nature Medicine. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01294-w. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- "B.1.1.7 Lineage with S:E484K Report". outbreak.info. 5 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- "Detection of SARS-CoV-2 P681H Spike Protein Variant in Nigeria". Virological. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- "Queensland travellers have hotel quarantine extended after Russian variant of coronavirus detected". www.abc.net.au. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- "Latest update: New Variant Under Investigation designated in the UK". www.gov.uk. 4 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "South Africa announces a new coronavirus variant". The New York Times. 18 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Wroughton, Lesley; Bearak, Max (18 December 2020). "South Africa coronavirus: Second wave fueled by new strain, teen 'rage festivals'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Mkhize, Dr Zwelini (18 December 2020). "Update on Covid-19 (18th December 2020)" (Press release). South Africa. COVID-19 South African Online Portal. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

Our clinicians have also warned us that things have changed and that younger, previously healthy people are now becoming very sick.

- Abdool Karim, Salim S. (19 December 2020). "The 2nd Covid-19 wave in South Africa:Transmissibility & a 501.V2 variant, 11th slide". www.scribd.com.

- Lowe, Derek (22 December 2020). "The New Mutations". In the Pipeline. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

I should note here that there's another strain in South Africa that is bringing on similar concerns. This one has eight mutations in the Spike protein, with three of them (K417N, E484K and N501Y) that may have some functional role.

- "Statement of the WHO Working Group on COVID-19 Animal Models (WHO-COM) about the UK and South African SARS-CoV-2 new variants" (PDF). World Health Organization. 22 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- "Novel mutation combination in spike receptor binding site" (Press release). GISAID. 21 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- "New California Variant May Be Driving Virus Surge There, Study Suggests". New York Times. 19 January 2021.

- "SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 24 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- "Local COVID-19 Strain Found in Over One-Third of Los Angeles Patients". news wise (Press release). California: Cedars Sinai Medical Center. 19 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- "B.1.429". Rambaut Group, University of Edinburgh. PANGO Lineages. 15 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "B.1.429 Lineage Report". Scripps Research. outbreak.info. 15 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "COVID-19 Variant First Found in Other Countries and States Now Seen More Frequently in California". www.cdph.ca.gov. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Weise, Karen Weintraub and Elizabeth. "New strains of COVID swiftly moving through the US need careful watch, scientists say". USA TODAY. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Delta-PCR-testen" [The Delta PCR Test] (in Danish). Statens Serum Institut. 25 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- "GISAID hCOV19 Variants (see menu option 'G/484K.V3 (B.1.525)')". www.gisaid.org. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- "Status for udvikling af SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern (VOC) i Danmark" [Status of development of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern (VOC) in Denmark] (in Danish). Statens Serum Institut. 27 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- "Varianten van het coronavirus SARS-CoV-2" [Variants of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2] (in Dutch). Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, RIVM. 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "A coronavirus variant with a mutation that 'likely helps it escape' antibodies is already in at least 11 countries, including the US". Business Insider. 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- "En ny variant av koronaviruset er oppdaget i Norge. Hva vet vi om den?" [A new variant of the coronavirus has been discovered in Norway. What do we know about it?] (in Norwegian). Aftenposten. 18 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- Cullen, Paul (25 February 2021). "Coronavirus: Variant discovered in UK and Nigeria found in State for first time". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 February 2021. Gataveckaite, Gabija (25 February 2021). "First Irish case of B1525 strain of Covid-19 confirmed as R number increases". Irish Independent. Retrieved 25 February 2021. McGlynn, Michelle (25 February 2021). "Nphet confirm new variant B1525 detected in Ireland as 35 deaths and 613 cases confirmed". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- "Japan finds new coronavirus variant in travelers from Brazil". Japan Today. Japan. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Faria, Nuno; Claro, Ingra; Candido, Darlan; Franco, Lucas; Andrade, Pamela; Coletti, Thais; et al. (12 January 2021). "Genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus: preliminary findings". CADDE Genomic Network. virological.org. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- Covid-19 Genomics UK Consortium (15 January 2021). "COG-UK Report on SARS-CoV-2 Spike mutations of interest in the UK" (PDF). www.cogconsortium.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "P.1 report". cov-lineages.org. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- Voloch, Carolina M.; F, Ronaldo da Silva; Almeida, Luiz G. P. de; Cardoso, Cynthia C.; Brustolini, Otavio J.; Gerber, Alexandra L.; Guimarães, Ana Paula de C.; Mariani, Diana; Costa, Raissa Mirella da; Ferreira, Orlando C.; Workgroup, Covid19-UFRJ (2020). "Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Figure 5". doi:10.1101/2020.12.23.20248598. Retrieved 15 January 2021 – via MedRxiv.

- "PANGO lineages Lineage P.2". COV lineages. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

P.2… Alias of B.1.1.28.2, Brazilian lineage

- Voloch, Carolina M.; F, Ronaldo da Silva; Almeida, Luiz G. P. de; Cardoso, Cynthia C.; Brustolini, Otavio J.; Gerber, Alexandra L.; Guimarães, Ana Paula de C.; Mariani, Diana; Costa, Raissa Mirella da; Ferreira, Orlando C.; Workgroup, Covid19-UFRJ (26 December 2020). "Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil". Le Phare de l'Esperanto. doi:10.1101/2020.12.23.20248598. ISSN 2024-8598. S2CID 229379623 – via MedRxiv.

- Voloch, Carolina M.; et al. (1 March 2021). "Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil" (PDF). Journal of Virology. ASM. doi:10.1128/JVI.00119-21. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Nascimento, Valdinete; Souza, Victor (25 February 2021). "COVID-19 epidemic in the Brazilian state of Amazonas was driven by long-term persistence of endemic SARS-CoV-2 lineages and the recent emergence of the new Variant of Concern P.1". Research Square. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-275494/v1. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- Andreoni, Manuela; Londoño, Ernesto; Casado, Leticia (3 March 2021). "Brazil's Covid Crisis Is a Warning to the Whole World, Scientists Say – Brazil is seeing a record number of deaths, and the spread of a more contagious coronavirus variant that may cause reinfection". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- Zimmer, Carl (1 March 2021). "Virus Variant in Brazil Infected Many Who Had Already Recovered From Covid-19 – The first detailed studies of the so-called P.1 variant show how it devastated a Brazilian city. Now scientists want to know what it will do elsewhere". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- Garcia-Beltran, Wilfredo; Lam, Evan; Denis, Kerri (18 February 2021). "Circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity". doi:10.1101/2021.02.14.21251704. Retrieved 3 March 2021 – via medrxiv.

- Gaier, Rodrigo (5 March 2021). "Exclusive: Oxford study indicates AstraZeneca effective against Brazil variant, source says". Reuters. Rio de Janeiro. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- "Exclusive: Oxford study indicates AstraZeneca effective against Brazil variant, source says". Reuters. Rio de Janeiro. 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- Simões, Eduardo; Gaier, Rodrigo (8 March 2021). "CoronaVac e Oxford são eficazes contra variante de Manaus, dizem laboratórios" [CoronaVac and Oxford are effective against Manaus variant, say laboratories]. UOL Notícias (in Portuguese). Reuters Brazil. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- News, ABS-CBN (18 February 2021). "DOH confirms detection of 2 SARS-CoV-2 mutations in Region 7". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Santos, Eimor (13 March 2021). "DOH reports COVID-19 variant 'unique' to PH, first case of Brazil variant". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- News, ABS-CBN (13 March 2021). "DOH confirms new COVID-19 variant first detected in PH, first case of Brazil variant". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- "PH discovered new COVID-19 variant earlier than Japan, expert clarifies". CNN Philippines. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- "Japan detects new coronavirus variant from traveler coming from PH". CNN Philippines. 13 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "UK reports 2 cases of COVID-19 variant first detected in Philippines". ABS-CBN. 17 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Maison, David P.; Ching, Lauren L.; Shikuma, Cecilia M.; Nerurkar, Vivek R. (7 January 2021). "Genetic Characteristics and Phylogeny of 969-bp S Gene Sequence of SARS-CoV-2 from Hawaii Reveals the Worldwide Emerging P681H Mutation". bioRxiv : The Preprint Server for Biology: 2021.01.06.425497. doi:10.1101/2021.01.06.425497. PMC 7805472. PMID 33442699. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

Available under CC BY 4.0. - Mandavilli, Apoorva; Mueller, Benjamin (2 March 2021). "Why Virus Variants Have Such Weird Names". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- Schraer, Rachel (18 July 2020). "Coronavirus: Are mutations making it more infectious?". BBC News. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "New, more infectious strain of COVID-19 now dominates global cases of virus: study". medicalxpress.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. (2 July 2020). "Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus". Cell. 182 (4): 812–827.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 7332439. PMID 32697968.

- "SARS-CoV-2 D614G variant exhibits efficient replication ex vivo and transmission in vivo". science.sciencemag.org. 18 December 2020. doi:10.1126/science.abe8499. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

an emergent Asp614→Gly (D614G) substitution in the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 strains that is now the most prevalent form globally

- COG-UK update on SARS-CoV-2 Spike mutations of special interest: Report 1 (PDF) (Report). COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium (COG-UK). 20 December 2020. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Butowt, R.; Bilinska, K.; Von Bartheld, C. S. (21 October 2020). "Chemosensory Dysfunction in COVID-19: Integration of Genetic and Epidemiological Data Points to D614G Spike Protein Variant as a Contributing Factor". ACS Chem Neurosci. 11 (20): 3180–3184. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00596. PMC 7581292. PMID 32997488.

- Greenwood, Michael (15 January 2021). ""What Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 are Causing Concern?"]". News Medical Lifesciences. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- "escape mutation". HIV i-Base. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- Wise, Jacqui (5 February 2021). "Covid-19: The E484K mutation and the risks it poses". The BMJ. 372: n359. doi:10.1136/bmj.n359. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 33547053. S2CID 231821685.

- "Brief report: New Variant Strain of SARS-CoV-2 Identified in Travelers from Brazil" (PDF) (Press release). Japan: NIID (National Institute of Infectious Diseases). 12 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- "Technical briefing 5" (PDF). Gov.uk. Public Health England. p. 17. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Greaney, Allison (4 January 2021). "Comprehensive mapping of mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human serum antibodies". doi:10.1101/2020.12.31.425021. S2CID 231615359. Retrieved 25 January 2021 – via bioRxiv. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rettner, Rachael (2 February 2021). "UK coronavirus variant develops vaccine-evading mutation - In a handful of instances, the U.K. coronavirus variant has developed a mutation called E484K, which may impact vaccine effectiveness". Live Science. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Achenbach, Joel; Booth, William (2 February 2021). "Worrisome coronavirus mutation seen in U.K. variant and in some U.S. samples". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "Researchers Discover New Variant of COVID-19 Virus in Columbus, Ohio". wexnermedical.osu.edu. 13 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Tu, Huolin; Avenarius, Matthew R.; Kubatko, Laura; Hunt, Matthew; Pan, Xiaokang; Ru, Peng; Garee, Jason; Thomas, Keelie; Mohler, Peter; Pancholi, Preeti; Jones, Dan (26 January 2021). "Distinct Patterns of Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Variants including N501Y in Clinical Samples in Columbus Ohio". bioRxiv: 2021.01.12.426407. doi:10.1101/2021.01.12.426407.

- "University of Graz". www.uni-graz.at. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- "Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (formerly known as Wuhan coronavirus and 2019-nCoV) - what we can find out on a structural bioinformatics level". Innophore. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- Singh, Amit; Steinkellner, Georg; Köchl, Katharina; Gruber, Karl; Gruber, Christian C. (22 February 2021). "Serine 477 plays a crucial role in the interaction of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with the human receptor ACE2". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 4320. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83761-5. ISSN 2045-2322.

- "BioNTech: We aspire to individualize cancer medicine". BioNTech. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- Schrörs, Barbara; Gudimella, Ranganath; Bukur, Thomas; Rösler, Thomas; Löwer, Martin; Sahin, Ugur (4 February 2021). "Large-scale analysis of SARS-CoV-2 spike-glycoprotein mutants demonstrates the need for continuous screening of virus isolates". bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.02.04.429765.

- "Study shows P681H mutation is becoming globally prevalent among SARS-CoV-2 sequences". News-Medical.net. 10 January 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- Smout, Alistair (26 January 2021). "Britain to help other countries track down coronavirus variants". www.reuters.com. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Donnelly, Laura (26 January 2021). "UK to help sequence mutations of Covid around world to find dangerous new variants". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Kupferschmidt, Kai (23 December 2020). "U.K. variant puts spotlight on immunocompromised patients' role in the COVID-19 pandemic". Science.

- Sutherland, Stephani (23 February 2021). "COVID Variants May Arise in People with Compromised Immune Systems". Scientific American.

- McCarthy, Kevin R.; Rennick, Linda J.; Nambulli, Sham; Robinson-McCarthy, Lindsey R.; Bain, William G.; Haidar, Ghady; Duprex, W. Paul (3 February 2021). "Recurrent deletions in the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein drive antibody escape". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abf6950.

- Office of the Commissioner (23 February 2021). "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Issues Policies to Guide Medical Product Developers Addressing Virus Variants". FDA. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Mahase E (March 2021). "Covid-19: Where are we on vaccines and variants?". BMJ. 372: n597. doi:10.1136/bmj.n597. PMID 33653708. S2CID 232093175.

- Muik A, Wallisch AK, Sänger B, Swanson KA, Mühl J, Chen W, et al. (March 2021). "Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 pseudovirus by BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited human sera". Science. 371 (6534): 1152–1153. doi:10.1126/science.abg6105. PMC 7971771. PMID 33514629.

- Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, Iketani S, Luo Y, Guo Y, et al. (March 2021). "Antibody Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 Variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2. PMID 33684923.

- Emary KR, Golubchik T, Aley PK, Ariani CV, Angus BJ, Bibi S, et al. (2021). "Efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2 VOC 202012/01 (B.1.1.7)". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3779160. ISSN 1556-5068.

- Mahase E (February 2021). "Covid-19: Novavax vaccine efficacy is 86% against UK variant and 60% against South African variant". BMJ. 372: n296. doi:10.1136/bmj.n296. PMID 33526412. S2CID 231730012.

- Kuchler H (25 January 2021). "Moderna develops new vaccine to tackle mutant Covid strain". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Liu Y, Liu J, Xia H, Zhang X, Fontes-Garfias CR, Swanson KA, et al. (February 2021). "Neutralizing Activity of BNT162b2-Elicited Serum - Preliminary Report". The New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/nejmc2102017. PMID 33596352.

- Hoffmann M, Arora P, Gross R, Seidel A, Hoernich BF, Hahn AS, et al. (March 2021). "1 SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and P.1 escape from neutralizing antibodies". Cell. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.036. PMID 33794143.

- "Pfizer and BioNTech Confirm High Efficacy and No Serious Safety Concerns Through Up to Six Months Following Second Dose in Updated Topline Analysis of Landmark COVID-19 Vaccine Study". Pfizer. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- "Johnson & Johnson Announces Single-Shot Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate Met Primary Endpoints in Interim Analysis of its Phase 3 ENSEMBLE Trial" (Press release). Johnson & Johnson. 29 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Francis D, Andy B (6 February 2021). "Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID shot less effective against South African variant: study". Reuters. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- "South Africa halts AstraZeneca jab over new strain". BBC News. 7 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- Booth W, Johnson CY (7 February 2021). "South Africa suspends Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine rollout after researchers report 'minimal' protection against coronavirus variant". The Washington Post. London. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

South Africa will suspend use of the coronavirus vaccine being developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca after researchers found it provided "minimal protection" against mild to moderate coronavirus infections caused by the new variant first detected in that country.

- "Covid: South Africa halts AstraZeneca vaccine rollout over new variant". BBC News. 8 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

External links

| Look up COVID in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "CoVariants". CoVariants.org. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- "Coronavirus Variants and Mutations". The New York Times.

- Corum, Jonathan; Zimmer, Carl (18 January 2021). "Inside the B.1.1.7 Coronavirus Variant". The New York Times.